China-ASEAN Cost of Business Comparisons – Executive Summary

We have just completed our nine part series on the

cost of doing business in ASEAN compared with China. The nine country

comparisons (see below for all links) detail cost of labor and taxes,

together with bilateral trade profiles between China and Cambodia, Laos,

Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Brunei was

omitted from the series as it is of limited interest to foreign

investors except in the oil and gas fields, while Singapore was compared

directly to operational costs in Hong Kong.

As the operational cost of doing business in China

continues to rise, some of the ASEAN nations start to become attractive.

But which ones? The ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement impacts on some

countries in different ways, and not all ASEAN members are in AEC

compliance as yet. Plus there are labor issues such as education and

workplace capabilities to consider. Also, some ASEAN countries wage

levels are not so far behind China. So where to go as a China

alternative is a complex issue.

What the series does do is demonstrate there is a

developmental hierarchy amongst ASEAN nations. I feel that Singapore and

Malaysia are developing extremely well in hi-tech and back office

capabilities. These are the support centers for ASEAN. Indonesia,

Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam all have great potential for

foreign investment manufacturing to then both re-export back to the

China market under the ASEAN-China FTA, while Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar

all face serious infrastructure issues and will take at least a decade

to reach potential.

ASEAN At A Glance

- Manufacturing, Financial & Support Services: Singapore & Malaysia

- Global Manufacturing: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand & Vietnam

- Just Getting Started: Cambodia, Laos & Myanmar

Concerning the latter three states, it should be

noted that none of them are currently in AEC compliance, which is

supposedly due at the end of this year. That means that they have not

yet reduced tariffs on imported goods, which also affects their free

trade status with China in particular. I suspect these three countries

may miss the end of year compliance deadline, as none of them have

manufacturing capabilities strong enough to withstand the onslaught of

tariff-free cheap Chinese goods that would then result. I wrote about

the AEC Compliance deadline and its impact here.

That doesn’t mean that investment from China and

other ASEAN nations isn’t going into these countries. But it does mean

that they may not yet be economically strong enough to be part of the

full ASEAN story just yet. Myanmar in particular has extensive problems

with human capital, they have plenty of people, but hardly any of them

have any training beyond local subsistence farming. That is a problem

when it comes to organizing a labor force.

Concerning ASEAN’s regional trade, a key factor is

the Free Trade Agreements ASEAN has with China, India and Australasia.

These are key game changers. The China-ASEAN FTA is already reshaping

where and when China based manufacturers and sourcing agents do business

in Asia. Not everything can now be manufactured to quality standards

and at inexpensive production costs in China. That agreement is shifting

the global supply chain. The ASEAN-India agreement is still being

developed; services has recently been added to that and this will assist

Indian entrepreneurs. It would be possible for example for an Indian

company to set up a manufacturing plan in ASEAN and then sell their

production, duty free, to China. Australians too have been so

concentrated on their recent FTA with China their ASEAN FTA has largely

been overlooked. Yet it is worth a huge amount to the Australian

economy. For example, the amount of iron ore required in ASEAN to

upgrade infrastructure is double that which China committed in the

financial crisis and which in its own right set off a mini construction

boom. After China, ASEAN and India are the next great Asian opportunities.

Overall, the series paints a comprehensive picture of

the development state of ASEAN as it is today. For China based

manufacturers looking to relocate part or all of their production, the

likes of Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam can each

be considered. In addition to this, it is becoming apparent that in

order to properly run and develop an ASEAN operation, and especially if

there is likely to be more than one location involved, Singapore and

Kuala Lumpur are the service centers to consider.

Dezan Shira & Associates meanwhile can assist

with country cost comparisons and dig deeper for corporate bespoke

intelligence. Please contact the firm at asia@dezshira.com

Links to the other articles in this series are as follows:

|

||||||||||

About Us

Asia Briefing Ltd. is a subsidiary of Dezan Shira & Associates.

Dezan Shira is a specialist foreign direct investment practice,

providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and

compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review

services to multinationals investing in China, Hong Kong, India,

Vietnam, Singapore and the rest of ASEAN. For further information,

please email asean@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com.

Stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends in Asia by subscribing to our complimentary update service featuring news, commentary and regulatory insight.

|

Ref;http://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/2015/05/28/china-asean-cost-of-business-comparisons-executive-summary.html

China-ASEAN Wage Comparisons and the 70 Percent Production Capacity Benchmark

Op-Ed Commentary: Chris Devonshire-Ellis

As wage increases in China continue to rise – along

with the comparatively high national welfare costs – increasing comment

is being made as to the legitimacy of the “China Plus One” scenario.

Coined some years ago, this theory – in reality, more of a shrewd

observation – suggests that future manufacturing capacity will be placed

both in China and externally in another location by the same

manufacturer.

In fact, this has been going on for years, most

notably between China and Vietnam. The recent anti-Chinese riots there

have even prompted Hong Kong Shippers’ Council chairman Willy Lin Sun-mo

to state that Hong Kong manufacturers based in the Pearl River Delta

are running out of alternative, low-cost factory locations

with ample labour following recent instability in their two preferred

destinations, Vietnam and Thailand. I wrote about the Vietnam and Thai

issues – along with a risk analysis for doing business in the rest of

Asia – and China, earlier this week here, in this article “Anti-China Vietnam Riots a Passing Phase,”

and Willy Lin’s comments can also be construed as a mild political

point to Beijing that placing oil rigs in disputed waters hurts Hong

Kong manufacturers.

But beyond the recent China-Vietnam clashes, what is

the real deal behind the China Plus One issue? Why haven’t thousands of

China-based factories closed in face of increasing costs? Where is the

economic point at which China wages become non-competitive? And is

China’s superior infrastructure the reason why manufacturing will stay

in China? These are all important strategic questions for both the China

based manufacturer, and the foreign investor to be asking. I will deal

with these issues as follows:

How High in Comparison to the Rest of Asia are China’s Wages?

This is not such a simple question to answer. Firstly

because China is a large country with a considerable variables in costs

of labour on a national basis. Secondly because the cost of employing

staff in China usually involves an additional expense in mandatory

social welfare contributions – as is also the case in other countries.

But to get a handle on this, we can look at indicators – and in this

case, compare the average minimum wage in China as against the other

primary manufacturing destinations in Asia. I have taken the main ASEAN

manufacturing nations as well as India to compare.

Note that this figure is average. That means that it

combines lower minimum wage levels in China with more expensive minimum

wage levels – which tend to be precisely where manufacturing labour is

required. The average China figure then is actually a bit lower than it

would be should we just take minimum wages around the manufacturing hubs

of Guangdong, Zhejiang and Jiangsu.

In this comparison, China looks competitive when

compared with Thailand and Malaysia. However, the minimum wage

comparison is only part of the story. What then kicks in, are mandatory

social welfare contributions. These need to be paid by the employer on

top of the salary, and are calculated on a percentage basis against

salary. There is some regional variation here, but not so much as to

make huge differences to the mean average.

To make it easier to break down, we can compare

regional wages, including the added social welfare component, against

China as follows:

In fact, they have been. The Hong Kong Federation of Industries

warned back in 2011 that some 16,000 Hong Kong owned factories were at

risk of closure. Of those, it is estimated about 30 percent actually

shuttered their doors. The figures for Taiwanese owned factories are

similar. Many slipped away to Vietnam or elsewhere. This movement has

largely gone unreported in international media as it has not tended to

involve Western investors to the same degree. However, what has been

happening is that the business model of many Western-invested factories

in China has changed. Instead of being limited to purely export-driven

manufacturing, the regulatory environment for foreign invested

manufacturers changed a decade ago to permit local production to be sold

onto the domestic China market. That was a game changer, and such

factories are now concentrating on servicing the China demand. Many are

also engaged in improving their China supply chain and distribution

networks. So the answer is, cheap Hong Kong/Taiwanese labour-intensive

factories aside, manufacturing investment in China has evolved to

service increasing China demand. Those factories are staying put.

At What Point Does Manufacturing in China Become Uncompetitive?

This question is actually industry specific. Many

manufacturers in China are doing very well, others not. We wrote about

the winners and losers in different types of industry in China recently

in this article, “South China’s Balancing Act Between Rising Wages and Keeping Investors Happy.”

But essentially, depending upon industry, the nature

of how some China based businesses began to become uncompetitive can be

traced back to January 1st, 2010. This is when the China-ASEAN Free

Trade Agreement came into effect. What this agreement broadly did was to

reduce the import/export duties on 90 percent of all products traded

between ASEAN nations and China. This impacted specifically on the more

advanced manufacturing nations of Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines,

Thailand and Vietnam. Initially, Chinese manufacturers had a field day

as they suddenly found these markets very close to home were completely

open, and cheap, labour intensive factories – many owned by the Hong

Kong and Taiwanese investors I mentioned earlier – flooded into these

countries.

But what has gradually been happening since then is

the consistent rise in Chinese labour costs. This has meant that

countries such as Vietnam are now highly competitive when measured

against China. But again, the issue is mainly industry specific, and

many factory operations are still highly profitable and likely to remain

so. China is moving up the value chain, and these industries are doing

well – for the time being. Labour intensive industries or those with

thin profit margins for error are however at high risk. For further

details and downloads of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, please

see our sister ASEAN Briefing website here.

Why China?

The big deal about China is its transition from

export manufacturing to a consumer-driven society. Briefly put, the

impact of this means that China’s middle class consumer population is

expected to rise from approximately 250 million today to 600 million by

2020. That means an additional 350 million middle class consumers will

emerge across China in the next seven years. The question then becomes

this. Where is the manufacturing capacity going to be to service those

consumers? The answer is Asia. The existing China operations will

evolve, and continue to provide some manufacturing facilities. But they

are also changing to become more logistics and planning based, even to

the extent of importing, warehousing and distributing products

manufactured in a related factory elsewhere in Asia. The China facility

is still needed, but its function is changing. And the big win is in

being able to sell to a Chinese consumer market more than doubling its

existing size. The real question then is whether the additional

manufacturing capacity required to service this market should be added

to the existing China facility or based in elsewhere in Asia.

Increasingly, the cost dynamics are in favour of it being placed

elsewhere in Asia. Hence the “China Plus One” issue.

The ASEAN-China Infrastructure Gap: 70 Percent Productivity is the Rule of Thumb.

Also kicking in to the entire picture is the

infrastructure issue. China’s infrastructure, and especially in South

China and the Zhejiang / Jiangsu regions is generally excellent, less so

once factories start to move inland. China actually has a serious

shortage of central and inland warehousing, distribution and logistics

facilities inland. However, there is still an infrastructure gap between

Shanghai for example and Ho Chi Minh City; Guangzhou and Manila and any

other permutations. Operating a factory in many ASEAN countries means

having to deal with an infrastructure not as well developed as on

China’s eastern seaboard, and this eats into productivity levels.

However, even this can be measured. As a general rule of thumb, when

asking Dezan Shira & Associates clients in Vietnam, Indonesia,

India, Philippines and elsewhere, it often makes economic sense to place

manufacturing capacity into a secondary location if the facility can

get production levels up to 70 percent of the equivalent operation

achievable in China. There is another caveat to this too. China wages

are only going to keep increasing. And additional investment means the

infrastructure gap is going to keep decreasing. In ten years’ time,

production managers are going to be far less likely to complain about

infrastructure problems elsewhere in Asia when held up against China.

Additional Profitability Issues

Another issue to bring into the equation is the rate

of profits tax. This is a moving target in Asia, although the situation

in China is quite consistent. Foreign investors who are taking the bulk

of their profits in China may also wish to examine the regional

alternatives. Dividends taxes apply to foreign investors who wish to

repatriate their profits back to their parent company.

Of these, it should be noted that several countries

are set to reduce taxes below that listed above. India, for example, is

expected to finally get its tax reform bill through Parliament, and this

is likely to see a reduction in CIT from 40 percent down to 30 percent.

The Philippines too has been discussing the same, with reductions to 25

percent. Vietnam has already said it will reduce CIT by 2016 also to 20

percent. These will make the economic debate concerning the placing of

additional manufacturing capacity into Asia much easier to acknowledge.

Withholding Taxes

It should be noted that use of applicable Double Tax

Treaties on certain charges such as services rendered by the parent

company as a strategy can decrease the amount of withholding tax

payable. This is commonly used to legitimately decrease the amount of

annual profits a company declares. Withholding tax rates on corporate

charges such as royalties are usually permissible at a 10 percent rate,

lower than the Profits tax rate. DTA typically reduce withholding taxes

by 50 percent. However all of the countries mentioned in our comparisons

already have significant DTAs in place, and there is not much benefit

to be gained over one or the other in this regard when compared with

China: nearly all have similar mechanisms in place. For an overview of

how Double Tax Treaties can impact upon your China operations, please

see our article on the subject here.

Investment Incentives & Tax Breaks

China essentially standardized its tax position a

decade ago and apart from a few examples, did away with many of the 15

percent profits tax rates and five year tax breaks that marked much of

the 1980’s and 1990’s that encouraged foreign investment to pour into

the country. Now restricted to specific key underdeveloped geographical

regions and highly specific sought after technologies, China isn’t so

much of a bargain hunting ground when it comes to such deals nowadays.

But that doesn’t mean the rest of Asia is the same, and far from it. All

ASEAN nations as well as India possess free trade, special economic and

export processing zones, many of them offering the same sort of tax

breaks and low tax rates that China did a decade ago. The list is too

long to reproduce in this article, although we did cover the subject in

this issue of Asia Briefing Magazine “An Introduction to Development Zones Across Asia.”

When it comes to ASEAN and India, there are many tax breaks and

investment incentives around just as there used to be in China – so do

your research and shop around.

Winners & Losers

For China, this is all gain. However, existing

China-based manufacturing facilities will need to evolve a different set

of skills, most notably in developing supply chain, distribution,

warehousing and marketing skills into new regional China markets. The

China facility will become not just a manufacturer, but also a

facilitator, and this will mean a change of focus in addition to scope

of business to take advantage of the new China consumer dynamic.

Winners in Asia as we stand today include Vietnam,

who are set to lower their corporate income tax rate to 20 percent

(against China’s 25 percent) by 2016 specifically to better compete.

India too, with a new government in place, has both the benefit of an

inexpensive, huge and growing labour pool, and an improving

infrastructure. China has itself recognised the growing importance of

India as a manufacturing hub to service the China market – the Chinese

government have offered to foot 30 percent of India’s US$1 trillion infrastructure development

requirements to allow this to happen. And as sage China watchers well

note, it is always wise to follow China’s State policy. Plus India also

has a massive consumer market – one reason Ford have placed their entire

non-U.S. auto manufacturing capacity into Gujarat.

In terms of India’s relationship with ASEAN – it

should be noted that it too has a Free Trade Agreement with ASEAN –

meaning that 90 percent of all trade and services between the two are

now duty free. This provides an added incentive to establish an ASEAN

manufacturing facility to service not just China, but ASEAN and the

Indian markets in one fell swoop.

The Philippines and Indonesia are also likely to do

well. Despite the recent row over maritime borders, these have been kept

to diplomatic levels and bilateral trade has been increasing. A booming

Manila gambling scene, away from the eyes of the Chinese secret service

and spectacular beach resorts are fuelling a Chinese tourism boom,

while wide usage of English language and again, an improving

infrastructure is seeing the Philippines become an Asian investment sweet spot.

Indonesia too, although the Jakarta traffic situation

remains dire, is also offering large numbers of competent labour, an

increasingly educated workforce and a sizable Chinese diaspora who have

seen first hand the management techniques employed in mainland China and

are setting up similar operations in Java.

There is a lot of truth to the notion that the Indonesian city of

Surabaya is set to become that countries equivalent of Guangzhou – yet

how many foreign investors have heard of it?

Malaysia also offers a number of joint venture

business parks, run along the proven Chinese model, and these too offer

tax incentives and breaks no longer available in mainland China. The

country is politically stable, and provides excellent infrastructure –

as anyone who has taken the highway from the Airport to downtown Kuala

Lumpur will testify.

On the cautious side, Thailand looks set for a period

of military rule, which until the country is considered politically

stable enough, is likely to put off some foreign investors. Yet when

viewed as a longer term play, it has excellent dynamics and is

strategically placed in the centre of ASEAN. This makes the country an

ideal base from which to reach out to ASEAN’s own consumer market, as

well manufacture to service China and beyond. This is the reason Volkswagen have decided to base their Asian production facility in Thailand –

reaching out to the ASEAN market, while their existing China operations

will continue to focus on the growing Chinese domestic market.

Other commentators may ask why I haven’t mentioned

Cambodia, Laos or Myanmar. While they may sound adventurous, the reality

is that none of these countries as yet have any significant

infrastructure in place. Salary levels may well be low, but generally

speaking the infrastructure gap is too wide at present to make them

viable except for perhaps smaller manufacturers willing to spend a great

deal of time, effort, education and investment into these countries.

Neither are their international tax obligations especially advanced –

Cambodia, for example, has signed no double tax treaties at all, with

anyone.

For the next decade, these countries will remain the

preserve of big ticket infrastructure developers and will remain a step

too far for many, although over time this will change – just as

countries like Vietnam and Thailand start to become expensive. But that

is some way off yet.

Conclusion

The “China Plus One” issue is not just a theory, it

has already arrived and is being put into practice. Foxconn, for

example, are in the process of relocating their entire assembly

operations for Apple products to Indonesia.

Much of South China’s shoe-wear and fabrics industry

has already set up shop in Vietnam and Bangladesh, the latter to such an

extent that Bangladesh is now the world’s second largest producer of

textiles – after China.

Operational and economic trends as we have seen

dictate that Chinese labour is and will continue to become more

expensive, while the Asian infrastructure gap is narrowing. Yet China’s

own domestic consumer market is growing, as are those in the rest of

Asia – ASEAN and India included. The locating of a secondary production

facility elsewhere in Asia is not just a theory, it is an economic

necessity. Foreign investors wishing to sell product onto the China

market must now start to compare the economic costs of doing that from

China with that of placing that capacity elsewhere into Asia, and using

the China-ASEAN DTA to avoid import duties.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner of Dezan Shira & Associates

– a specialist foreign direct investment practice providing corporate

establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance,

accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to

multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in

1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service

consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India,

Singapore and Vietnam, in addition to alliances in Indonesia, Malaysia,

Philippines and Thailand, as well as liaison offices in Italy, Germany

and the United States. For further information, please email asia@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com.

Stay up to date with the latest business and investment trends in Asia by subscribing to our complimentary update service featuring news, commentary and regulatory insight.

Ref;http://www.china-briefing.com/news/2014/06/03/china-asean-wage-comparisons-70-production-capacity-benchmark.html

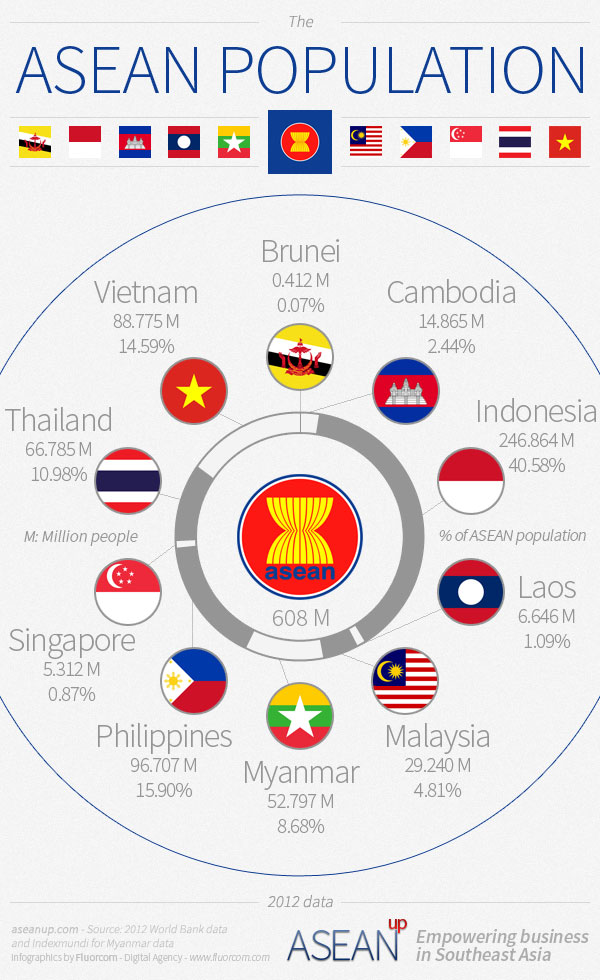

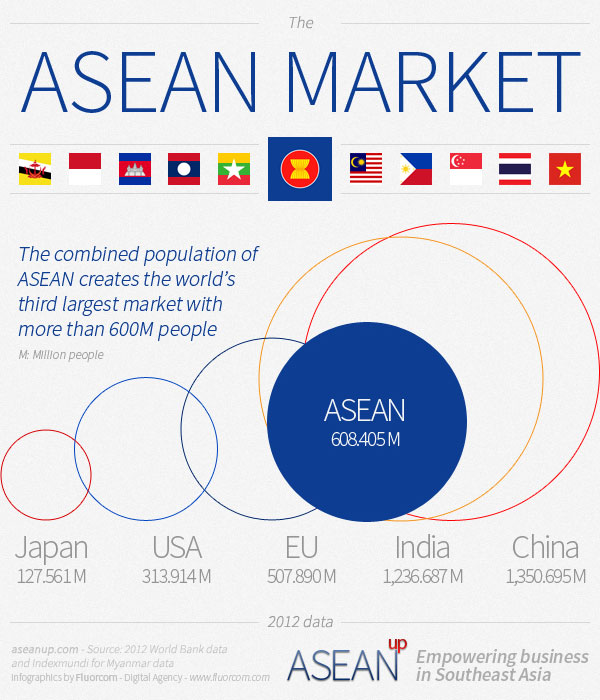

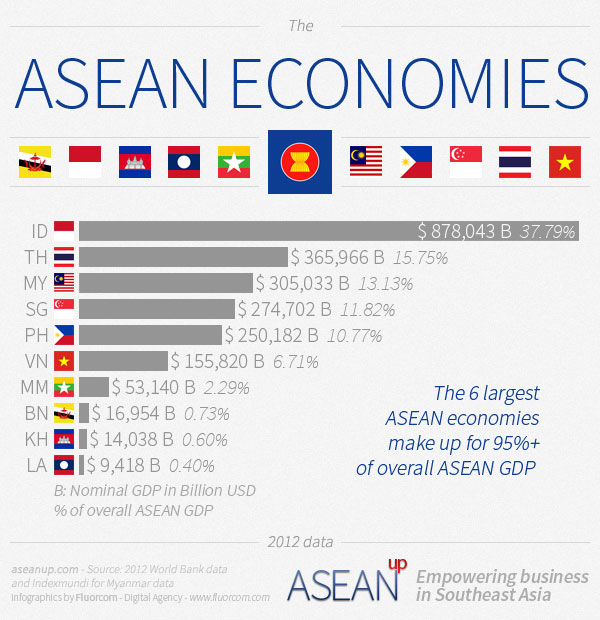

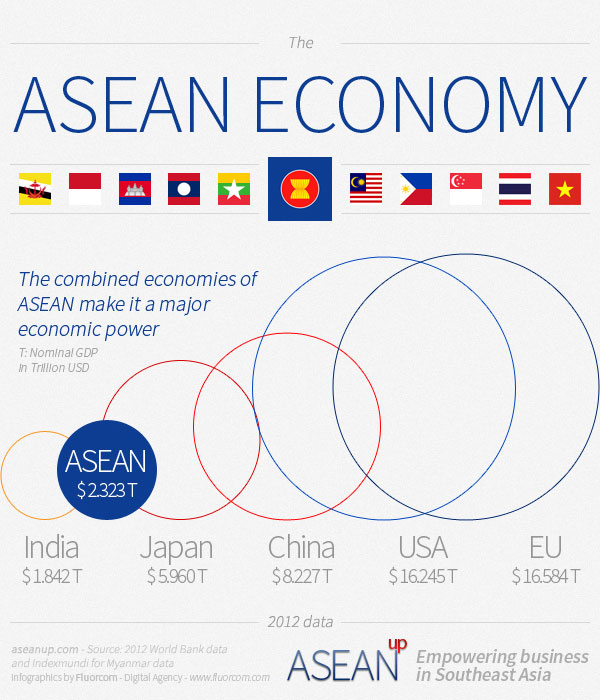

ASEAN infographics: population, market, economy

Here is a set of 4 individual infographics on the

share of each country in the population of ASEAN, the comparisons of

their economies as well as the aggregated ASEAN economy and market

compared to other major global market and economies: EU, US, China,

Japan and India.

Revised 15 March 2015

The following infographics present the data of the bigger “Why ASEAN: Economy & Demography Infographic”

with a focus on each of the main points. They can therefore be used

independently as needed for ASEAN presentations, websites, blogs,

illustrations, etc. with an interest on a particular point: economy,

population, market, comparisons…

ASEAN population

These two graphics present comparisons of the

population from within, between the 10 member countries, and from

outside, as a single market compared to other major markets.

Share of each country in the population of ASEAN

Embed code: ASEAN population

ASEAN market compared to the EU, US, China, Japan and India

Embed code: ASEAN market

ASEAN economy

These following two visuals show the important

differences in size of the economies of the ten ASEAN countries, but

also that they form together one of the largest economy in the world,

notably larger than India.

Compared GDPs of ASEAN countries

Embed code: ASEAN economies

ASEAN economy compared to the EU, US, China, Japan and India

Embed code: ASEAN economy

Related posts

ASEAN infographic: economy and demography

ASEAN infographic: economy and demography Connecting the ASEAN community

Connecting the ASEAN community Overview of the US-ASEAN relations

Overview of the US-ASEAN relations

No comments:

Post a Comment