That makes it hard for the new, democratic government to offer decent public services.

| YANGON

INSIDE a noodle house in central Yangon, business is

buzzing. Customers huddle over tables, slurping down chicken soup or

gobbling dumplings. Everyone pays in cash. Few customers ask for

receipts. When your correspondent does so, one is handed over, complete

with government-issued stickers. But the cost of the meal goes up. On

the vast majority of the restaurant’s sales, it seems, no one is paying

any tax.

Over the past decade the Burmese economy has

boomed. Last year it grew by 5.9%. In the medium term growth is expected

to average 7.1% a year, according to the World Bank, making the country

one of the peppiest in the region. Poverty, though still stark, has

fallen.

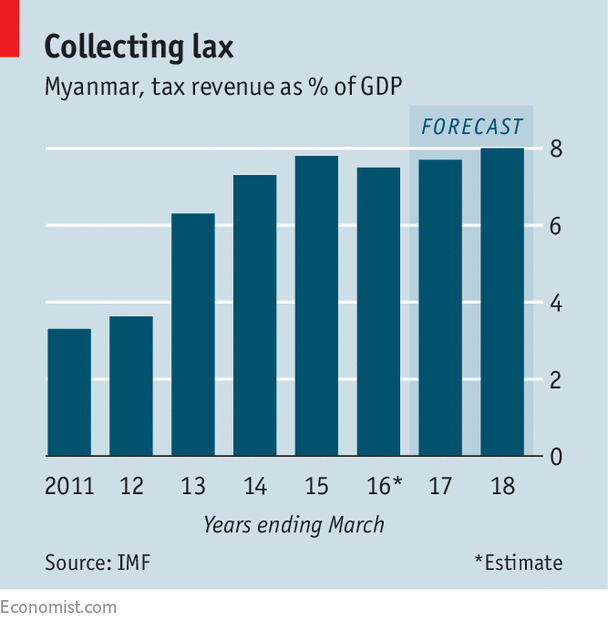

Yet

Myanmar has the lowest tax take in South-East Asia and one of the

lowest in the world, at a meagre 7.5% of GDP. That compares with 16% in

Thailand and 14% in Cambodia. Under Myanmar’s military rulers, the

picture used to be even worse. In 2011 the government collected less

than 4% of GDP. That year, however, Thein Sein, the general who had just

become president, launched an economic reform programme that included

opening an office responsible for collecting tax from big firms. By 2015

government revenue had more than doubled (see chart). It has since

stagnated.

The

generals permitted free elections in 2015, allowing the National League

for Democracy to come to power. Among its priorities are clamping down

on corruption and broadening the tax base. Businessmen complain that

taxmen gouge them for bribes, not revenue for the state. Humbler

citizens, meanwhile, tend not to pay tax on their income.

Other

taxes are routinely dodged, too. In order to avoid paying property

taxes, some buyers and sellers, or landlords and tenants, create two

contracts: one recording the actual transaction and a dummy to be

submitted for tax purposes, says Lachlan McDonald, an economist at the

Renaissance Institute, a think-tank in Yangon. Most Burmese donate money

to Buddhist temples or other religious institutions as a matter of

course. Handing money over to the exchequer is a far less common

activity.

“People do not want to pay tax because they

have never had much from the government,” says Matthew Arnold of the

Asia Foundation, an American NGO. Under the military regime, generals

made money from jade, narcotics and construction; Burmese without

connections made so little money there was little point asking them for

any. As a result, municipal services, which are meant to be paid for

through local taxes, were and are scant. In Yangon the official

municipal charge for rubbish collection is a token 600 kyats ($0.44) a

month. But a resident complains that to get the rubbish taken away, she

must pay informal street-cleaners an extra 200 kyats a bag.

It

does not help that the system for collecting taxes is hopelessly

antiquated. Assessments for property taxes are based on poor proxies for

value such as the number of storeys in a building and the materials

from which it is built. There is no effort to account for inflation. All

the relevant information is kept on paper, with almost no digital

records. According to Michael Lwin of Koe Koe Tech, a firm that has

launched a pilot scheme to allow local governments to offer services

online, this system puts the average annual rental value of the 23,516

recorded properties in the relatively affluent city of Taunggyi at $21,

when in practice buildings are let out for much more. Even if tax

collectors really intended to raise money for the government, it would

be hard to collect much.

The city government in Yangon,

the commercial capital, has set up an office to check up on a broader

range of potential taxpayers, beyond the big fish. But the NLD

government may be facing a Catch-22: it will be hard to persuade Burmese

to pay tax unless they receive some services in return, but it will

also be hard to offer decent services without collecting some tax.

Ref:https://www.economist.com/news/asia/21731437-makes-it-hard-new-democratic-government-offer-decent-public-services-myanmar-has

No comments:

Post a Comment