Can Myanmar make it easier for SMEs to do business locally?

The World Bank released its Doing Business report for Myanmar in 2017.

Based on the findings, Myanmar ranks 170 in ease of doing business this year, up from 171 in 2016. The country now has a population of almost 54 million, and a gross national income per capita US$1,293 per year.

At 170, Myanmar actually trails all its neighbours in ASEAN in the ease of doing business (see Chart 1). But it is aiming to raise its rank to at least 100 or less within the next few years.

Published every year, Doing Business sheds light on how easy or difficult it is for a local entrepreneur to open and run a small to medium-size business when complying with relevant regulations. It measures and tracks changes in regulations affecting 11 areas in the life cycle of a business.

The report then presents results for two measures, a distance to the frontier (DTF) score and a ranking for the ease of doing business. The ranking of an economy is determined by sorting the aggregate distance to frontier scores. An economy’s distance to the frontier score is indicated on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 represents the worst performance and 100 the frontier.

Among the 11 areas highlighted in the report, regulatory changes and procedures in starting a business is an important indicator affecting a country’s rank in the ease of doing business index.

We discuss four out of the 11 areas here:

Chart 1. Myanmar ranks 170 out of 190 countries and is the least favourably ranked among comparable economies in the region on ease of doing business. It wants to raise its rank to 100.

Starting a business

In 2017, Myanmar made starting a business easier by reducing the cost to register a company. It also simplified the process by removing the requirement to submit a reference letter and a criminal history certificate to incorporate a company.

This was over and above eliminating the minimum capital requirement for local companies and streamlining corporate procedures in 2016, according to Doing Business.

Today, starting a business here requires 11 procedures, takes 13 days and costs 40.4 percent of income per capita for both men and women (Chart 2). Income per capita is the average income earned per person in a given area. In Asia, Myanmar ranks higher than Indonesia, India and Laos when it comes to ease of starting a business.

Chart 2. What it takes to start a business in Myanmar: 11 procedures, 13 days and 40.4 pc of income per capita.

Getting electricity

Access to affordable and reliable electricity is also vital for businesses to conduct their operations here. In Myanmar, Doing Business finds that getting electricity requires a total of six procedures, takes 77 days and costs 1270pc of income per capita (Chart 3).

Chart 3. What it takes to obtain an electricity connection in Myanmar: 6 procedures, 77 days and 1,270 pc of income per capita

Myanmar has not done so well on this front and more action is needed. It now ranks above just Laos in ease of getting electricity in the region.

“Myanmar cannot produce electricity itself. If the electricity tariff is increased, people cannot pay. If tariff is not increased enough, investments cannot be made,” said Dr Soe Tun, a local businessman.

“Hydropower involves a huge investment, but producing electricity from coal can damage the environment. It is like a vicious cycle. Without electricity, it is difficult to implement other plans,” he said.

Getting credit

Chart 4. Economy scores on strength of legal rights for lenders and borrowers. Myanmar’ scored the lowest among other comparable economies in the region.

Access to credit is another important area in the ease of doing business. However, Myanmar is far behind every country in Asia when it comes to getting credit. Currently, legal rights for borrowers and lenders are almost non-existent and there is no credit information available in the market (Charts 4,5).

“It is very difficult to get loans in Myanmar because the interest rate is too high. So, starting a business is very difficult. Without solving this issue, businesses will not be able to do proper business,” Myanmar Rice Federation executive member U Thaung Win said.

“Myanmar must reduce its interest rate on loans. To do so, it must reduce the interest rate on deposits. Inflation must be low and stable. When inflation can be managed, it will be easier to reduce the interest rate on loans,” said economist Dr. Aung Ko Ko.

Chart 5. Economy scores on depth of credit information index. Myanmnar has a score of zero, implying no information is avaialble for lenders.

Cross border trade

In most economies, trading across borders has become faster and easier over the years as governments introduce processes like risk –based inspections and electronic data interchange systems to facilitate trade and competitiveness and reduce illegal dealings.

But Myanmar is at the bottom of the list when it comes to trading across borders. In 2017, it actually made cross border trade more difficult with delays and higher process costs for incoming cargo at the Yangon port, according to Doing Business. Illegal trade is also a big issue for the countr (Chart 6).

Chart 6. Summary of Myanmar on the ease of trading across borders. It’s getting harder to engage in cross border trade with the country. Source for charts: Doing Business

From 170 to 100

So can Myanmar hit its target rank of 100 or less in ease of doing business? What needs to be done? Here’s what some experts told The Myanmar Times:

Vice President U Myint Swe at the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI) office on July 20:

“Some [countries] may have good rankings but their prospects are not good. For example, in our neighboring countries, there are frequent damages to assets due to floods. Although Myanmar is low in the ease of doing business ranking, our prospects are better. We have fewer natural disasters, cheap labor and talent. Some are very eager to invest in Myanmar.”

Dr Soe Tun, local businessman:

“To raise our rank in the ease of doing business, problems with basic infrastructure, transaction cost and bureaucracy must be resolved and legal and systematic border trade must be established. Everything can’t be done at once, but we should solve what we can first.”

Dr Aung Ko Ko, economist:

“It’s great that there’s an ambition to do something. We won’t know exactly what the improvements are going to be. But, I’m sure that it will be better than the current situation. The constitution will have to be changed. Every sector will have to be reformed. If we do these things, I think things will improve gradually.”

U Tun Tun Naing, permanent secretary of the Ministry of Planning and Finance:

“The submission of work approvals takes a long time, so we can set up a faster one-stop service than the previous one. But, there are still many other things left. For example, getting electricity, and submitting the recommendation letters. The plans are set in motion and all the ministries are also cooperating.”

Knowing the history of Small and Medium Enterprises, SMEs in Myanmar

Myanmar has adopted the market – oriented economic system in 1988. Appropriate measures has been undertaken, the underlying aspect in doing so are decentralizing the central control, encouraging private sector development, allowing foreign direct investment, initiating institutional changes and promoting external trade by streamlining export and import producers. According, laws, orders, rules, regulations and notifications which had prohibited or restricted the private sector from engaging in economic activities were replaced and many laws and rules were amended to be in line with the change of time and circumstances.

The Union of Myanmar Foreign Investment Law (FIL) was enacted in November 1988 and the procedures prescribed in December 1988 encouraging foreign direct investment. Myanmar has opened the doors to foreign investment to participate actively in exploiting the natural resources thereby enhancing long – term mutually beneficial cooperation.

Myanmar has been implementing the National Development Plan with the aim to accelerate growth, achieve equitable and balanced development and to reduce socio – economic development gap between rural and urban areas of the country. A country’s economic development depends on micro economic stability. The country would see an increase in micro economic indicator, which generates more job opportunities, more exports and increase in balance of payment (BOP) ratio.

Myanmar is home to 70% of rural population and 30% of urban population, and most of the rural people are in poverty. The government is undertaking eight – point task of development and poverty alleviation for providing assistance for the rural people. According to the calculation of UNDP and UNICEF, poverty rate of the nation declined to 26% in 2010, compared with 32% in 2005. At present, those eight tasks of rural development and poverty alleviation campaign are being implemented with the aim of reducing the poverty rate to 16% in 2015.

Government is making great strides in carrying out necessary reforms with might and main for participating democracy correctly in all sectors and in every corner of the country. Regarding lifting of most economic sanctions against Myanmar, foreign investors are packing their suitcase for visit the Southeast Asia country in pursuit of business prospect. Recent changes in Myanmar can draw the attentions of foreign investors. Based on the foreign investments, domestic companies’ productivity would increase, thereby spurring the country’s economic growth. But, investments of foreign companies alone cannot increases productivity not including the domestic companies. All countries in the world have agreed the Foreign Direct Investment can push the economic development.

Current economic situations in Myanmar (Burma)

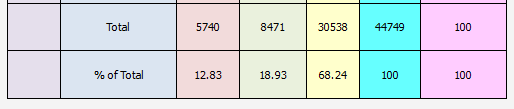

As Myanmar is still an agricultural country, the contribution to GDP by agriculture, livestock, fisheries and forestry accounted to 41.2%, while the processing and manufacturing sector accounted for about 21.7% and service sector account 37.1% at 2011-2012. For the Industry sector, principal manufacturing activities are related to the processing of agricultural resources with food and beverage production generating more than half of the gross manufacturing output followed by construction material industries contribution 7.58% and Garment industries contribution 4.83% of the total. Actually, Myanmar’s economic structure is early stages of industrialization.Thefollowing table shows the number of registered enterprises in each state and region of Myanmar according to the SMEs definition based on 2011 Private Industry Law.

Number of Registered Enterprises in States and Regions up to February, 2015

World Trade In Goods Of The ASEAN Countries (2011)

World trade in goods of the ASEAN countries (2011)

The graphics show the trade in goods of the ASEAN countries with the world, and in particular with China, EU27 and the NAFTA countries (USA, Canada and Mexico). The green section above refers to exports and the red part, below, to imports. Data are presented in euros after conversion from dollars using the annual average conversion rate from Eurostat.

The pie chart shows the share that China, EU and NAFTA countries represent for the ASEAN countries in terms of exports/imports of goods. For example, the ASEAN countries export merchandise to the world worth €887 billion. The part that goes to the EU represents 10.7% of their total exports, with a value of €95 billion.

The bar chart represents the total value of exports/imports from/to the ASEAN countries to/from China, EU and NAFTA in billion euros, with a breakdown for each of the ASEAN countries. For instance, the value of exports from Singapore to the EU27 was €28 billion, while Singapore’s imports from the EU amounted to €33 billion.

The pie chart shows the share that China, EU and NAFTA countries represent for the ASEAN countries in terms of exports/imports of goods. For example, the ASEAN countries export merchandise to the world worth €887 billion. The part that goes to the EU represents 10.7% of their total exports, with a value of €95 billion.

The bar chart represents the total value of exports/imports from/to the ASEAN countries to/from China, EU and NAFTA in billion euros, with a breakdown for each of the ASEAN countries. For instance, the value of exports from Singapore to the EU27 was €28 billion, while Singapore’s imports from the EU amounted to €33 billion.

EU27 Trade In Goods With The ASEAN Countries (2011)

EU27 trade in goods with the ASEAN countries (2011)

The graphic represents the exports/imports of EU27 countries to/from each of the ASEAN countries, with a breakdown by SITC (Standard International Trade Classification) product group.

SITC 0, 1: food, drink and tobacco

SITC 6, 8: other manufactured goods

SITC 2, 4: raw materials

SITC 7: machinery and transport equipment

SITC 3: mineral fuels

SITC 5: chemical and related products

SITC 9: other goods

The green part represents exports and the red imports.

For both sections the units used are billion euros, shares of the total of the ASEAN country, and shares of the ASEAN countries in the total trade of the specific SITC product. The share has been calculated based on extra-EU trade, i.e. excluding trade between Member States.

SITC 0, 1: food, drink and tobacco

SITC 6, 8: other manufactured goods

SITC 2, 4: raw materials

SITC 7: machinery and transport equipment

SITC 3: mineral fuels

SITC 5: chemical and related products

SITC 9: other goods

The green part represents exports and the red imports.

For both sections the units used are billion euros, shares of the total of the ASEAN country, and shares of the ASEAN countries in the total trade of the specific SITC product. The share has been calculated based on extra-EU trade, i.e. excluding trade between Member States.

As an example, total EU exports to the ASEAN countries amounted to €69 billion. €27.2 billion of merchandise has been exported to Singapore, with this amount representing 1.74% of total EU exports. In terms of product group, the EU exported €34.8 billion of “machinery and transport equipment” to the ASEAN countries, which represents 5.3% of all EU exports of this product category to the world.

The sum of the SITC product categories are less than the total due to confidentiality reason.

NB Variations between figure 1 and 2 are due to the data coming from different sources and currency conversion.

The sum of the SITC product categories are less than the total due to confidentiality reason.

NB Variations between figure 1 and 2 are due to the data coming from different sources and currency conversion.

Ref:https://epthinktank.eu/2013/02/26/eu-asean-trade-relations/fig-2/

Myanmar Government Prioritizes the Development of SMEs

The Myanmar government is making efforts to transform the political, economic and

social environment to be in line with global changes, and to promote sustainable economic

growth. This includes promoting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which play a

pivotal role in the economic development of both developing and developed countries.

Myanmar has a vision to develop SMEs, based on the policy to create regionally

innovative and competitive SMEs across all sectors, to stimulate income generation, and

contribute to socio-economic development. Various studies estimate that SMEs in Myanmar

account for 50-95 percent of employment, and contribute 30-53 percent of the country’s GDP.

According to the Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SME) Development Bill (SME Bill),

which was launched in January 2014, “small enterprises” are defined as those with K50 to K500

million in capital, or with 30-300 employees. “Medium-size” firms are defined as those with K50

million to K 1 billion in capital, or with 60-600 employees. As a result, 99.4 percent of business

in Myanmar are approximately classified as SMEs, and there are now 50,694 SMEs altogether in

the regions and states on Union territory.

In Myanmar, SMEs are considered important to the national economy. They create a lot

of job opportunities for the population and contribute to employment and income generation,

resource utilization, and promotion of investment. For this reason, the Myanmar government has

given special attention to the development of SMEs, support for existing SMEs to become larger

industries, and creating a conducive business environment for SMEs. The SME Development

Central Committee’s Joint Chairperson, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, stated at one

committee meeting that SMEs cannot be ignored, as they make up 99 percent of Myanmar’s

economic force.

With regard to SMEs, the government has prioritized human resource development,

support for technical development and innovation, capital funding, better infrastructure, gaining

a foothold in the marketplace, reasonable taxes and regulations, and the creation of suitable

businesses. A new policy to promote the development of SMEs includes tax relief and tax

exemptions, since SMEs in Myanmar suffer from arduous tax and monetary policies. They also

suffer from lack of access to capital and protection of intellectual property, as well as high

interest rates, and lack of close relations with Myanmar banks. However, on 1 August 2017, the

State Counsellor met with the Chair of 22 Myanmar banks in Nay Pyi Taw, and urged them to

cooperate with the government in promoting Myanmar’s economic growth. SMEs and

businessmen hope that this meeting will benefit SMEs and the business sector.

Financial Support for SMEs.

The Myanmar government provides only non-financial assistance to business enterprises,

due to limitations on the government budget. However, thanks to the Financial Support for SMEs

policy, the Myanmar Economic Bank (MEB), Myanmar Investment & Commercial Bank

(MICB) and Myanmar Industrial Development Bank (MIDB) have provided loans to SMEs since

2004. The state-owned Myanmar Agriculture Development Bank has also provided loans to farmers throughout the country. At the same time, banks are trying to reduce the interest rate on

loans in order to contribute to national economic development. They have proposed that interest

rates be reduced from 17 percent to 15 percent. Banks and the Ministry of Agriculture are also

working together to provide financial support towards the development of rural areas and rural

livelihoods. For example, state-owned Myanmar Agriculture Development Bank has provided

small loans to farmers, the fishery sector and rubber plantations.

In addition, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) will provide a K 15 billion loan through the government to develop SMEs in 2017 at a low interest rate. The

loan is granted through the Myanma Economic Bank (MEB), and SMEs and businessmen who

apply for the loan are required to submit their current business situation and future program of

their businesses to the SMEs Development Department. Nevertheless, despite the increasing

provision of loans, the lack of financial access and high tax rates still restrict the development of

SMEs in Myanmar.

SMEs Development.

Myanmar’s business environment is undergoing a lot of rapid changes. However, SMEs

in Myanmar face many challenges during the period of political and economic transition. New

trends have to be taken into account continuously, such as growing demand and customers’

expectations on flawless products and services. Moreover, SMEs are facing increasing global

competition, the emergence of new technologies and impact on integrated supply chain and

production systems among ASEAN member states. In Myanmar, challenges to SMEs are varied

and complex, depending on the sector and level of development. Common challenges include

financial access, human resource development, R&D in technology, management, and

marketing.

The Secretary of the Central Committee for the Development of SMEs, U Khin Maung

Cho, explained that in order to promote the skills of employees in SMEs, annual courses, such as

mobile vocational training courses, have been arranged and extended to rural areas. To narrow

the development gap among regions and states, 53 branch offices to support SMEs development

have been opened in 15 regions and states, including Nay Pyi Taw. In addition, Kasikorn Bank

(KBank) of Thailand also signed a MoU with the Central Department of Small and Medium

Enterprises Development (CDSMED) under the Ministry of Industry, to educate SMEs in

financial management, with a focus on business plans and accounting, starting in 2017. The

training seeks to strengthen SMEs in market competitiveness, technology, financial management,

and market compliance on their products.

In conclusion, the development of SMEs is important for the country’s economic

development, as they are major contributors to the economy and job creation. However, SMEs

are confronted with numerous challenges, including insufficient financial support, electric power

supply and credit guarantee. Given that SMEs form the backbone of the country’s economy,

economists have called on the government to improve the banking sector, and encourage banks

to provide more loans to SMEs at a reasonable interest rate. At the same time, capacity building

in areas such as business management, accounting, taxation, marketing management, human resource management, and capital management are in huge demand for SMEs to promote job

opportunities and socio-economic development. Thus, the development of SMEs in Myanmar

requires a concerted effort by government, banks, and private sector that can provide training, to

help SMEs reach their full potential in contributing towards Myanmar’s economic development.

References:

http://www.moi.gov.mm/moi:eng/?q=news/27/02/2017/id-10038

https://www.charltonsmyanmar.com/myanmar-economy-3/smes-in-myanmar/

http://www.president-office.gov.mm/en/?q=briefing-room/news/2017/03/03/id-7350

http://www.asean.org/storage/images/archive/documents/SME%20Development%20Policies%2

0in%204%20ASEAN%20Countries%20-%20Myanmar.pdf

http://www.asean.org/storage/images/archive/pdf/sme_6.pdf

http://texia.co/myanmars-smes-tax-disadvantages/

https://www.mmtimes.com/business/27310-state-counsellor-urges-bankers-to-promote-

economic-development.html

https://consult-myanmar.com/2017/08/19/more-smes-tap-myanmars-potential/

https://www.mmtimes.com/national-news/nay-pyi-taw/25525-myanmar-smes-to-get-a-boost-

from-thai-bank.html

SME in Myanmar

Advising Small and Media Sized Enterprises in Myanmar

Charltons provides focused legal advice to small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in Myanmar. SMEs play a crucial role in the economic well-being of developed and developing countries alike. 126,237 or approximately 99.4% of all businesses in Myanmar are classified as SMEs. On average, SMEs in Myanmar account for 50-95% of employment and contribute 30-53% of GDP in ASEAN member states. The Government recognizes that SME entrepreneurship will define the country’s future national economic development. However, international isolation and a lack of private sector investment, among other factors, have left Myanmar playing catch-up with its regional neighbours. Time is of the essence. With the ASEAN Free Trade Area coming into full effect by 2015 SMEs in Myanmar will no longer be able to rely on government tariffs to protect them from overseas competition. By the same token, the opening up of regional markets represents an enormous opportunity for SMEs in Myanmar but only if they are ready and able to meet the new challenges ahead.

In January 2014 the Government published the Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SME) Development Bill (SME Bill). The SME Bill defines “small enterprises” as those with between K50 million (approximately US$50,000) and K500 million (approximately US$500,000) in capital, or with between 30 -300 employees.

“Medium-size” firms are defined as having between K50 million (approximately US$50,000) and K1 billion (approximately US$1 million) in capital or between 60 and 600 staff.

Pursuant to Chapter 10 of the SME Bill, SME owners need to register their businesses and abide by the law in order to qualifiy for the various incentives contained in the bill. When a company exceeds the SME capital or employee thresholds, it must change its registration details.

SMEs in Myanmar | The Central Committee for SME Development

The Government has recently established a central committee to encourage SME development. The 27-member Central Committee for SME Development (SME Committee) which is chaired by President U Thein Sein has been tasked to formulate and promulgate laws, regulations and procedures to facilitate SME growth. It is also responsible for ensuring that both the government and private banks provide finance to SMEs in Myanmar, and for establishing an SME support networks in both rural and urban areas. Although well intended, it is unlikely that the SME Committee – which will include 20 ministers – will be free of politics. There are already numerous government departments, agencies and institutions promoting SME development in Myanmar. However, to date, a lack of will, inter-ministry cooperation, available finance and meaningful public-private partnerships has meant that in many respects, SMEs in Myanmar have being left to thread their own path.

The SME Committee should recognize the need to establish a semi-state body or authority to implement Government initiatives based on an SME development strategy. It is vital that the SME Committee be allowed to carry out its work free from excessive government interference. SME development requires the existence of institutions and support structures and the participation of a broad range of stakeholders. A properly funded SME state agency should link government departments, private business community, educational and technological institutions. It should also act as a conduit between SMEs and local and international lending institutions.

The development of Myanmar’s inadequate and degraded infrastructure is a national issue, as is the modernisation of the country’s power and telecommunications industries. Progress is both welcome and ongoing. Similarly it will take years for outdated technologies to be replaced and investment in local R&D to bear fruit. However the Government – or rather a new semi-state agency or agencies mandated to support SMEs – could immediately begin helping SMEs in Myanmar overcome a number of the unique challenges they face. Many companies, especially those hoping to target the export market or even foreign residents need to upgrade their products and services to meet international standards. In this respect the state should actively encourage business visitors and the participation of international suppliers in local trade fairs and exhibitions. It should also seek to curb the monopoly of larger enterprises and where applicable, allow SMEs to enter previously restricted markets. The Government must recognise, through both competition and inter-company cooperation, that SMEs promote innovation and skill levels in an economy. Above all else the Government must urgently pursue policies aimed at securing access to finance for the country’s SMEs. Without access to finance, business will not be able to cycle off inefficiency and low productivity which springs from a lack of capital investment. In tandem with tackling bank lending the government must introduce policies and legislation in relation to management best practices management and corporate governance which reflect international norms. An SME state agency should provide assistance and organise seminars, workshops and exhibitions at home and abroad to facilitate the interaction of its own SMEs with their regional counterparts, suppliers and potential clients. At present the Ministry of Industry is responsible for the development of SMEs in Myanmar and has established The Central Department of Small and Medium Enterprises Development.

Ref:https://www.charltonsmyanmar.com/myanmar-economy-3/smes-in-myanmar/

SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISE SURVEY MYANMAR 2015 by Than Han on Scribd

No comments:

Post a Comment