2012 Rakhine State Riots

| 2012 Rakhine State Riots | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Persecution of Muslims in Myanmar | |

| Location | Rakhine State, Myanmar |

| Date | 8 June 2012 (UTC+06:30) |

Attack type

| Religious |

| Deaths |

October: at least 80[4]

100,000 displaced[4]

|

The 2012 Rakhine State Riots were a series of conflicts primarily between ethnic Rakhine Buddhists and RohingyaMuslims in northern Rakhine State, Myanmar, though by October Muslims of all ethnicities had begun to be targeted.[5][6][7] The riots finally came after weeks of sectarian disputes including a gang rape and murder of a Rakhine woman by Rohingyas and killing of ten Burmese Muslims by Rakhines.[8] On 8 June 2012, Rohingyas started to burn Rakhine's Buddhist and other ethnic houses after returning from Friday's prayers in Maungdaw township. More than a dozen residents were killed in this riot by Rohingya Muslims.[9] State of emergency was declared in Rakhine, allowing military to participate in administration of the region.[10][11] As of 22 August, officially there had been 88 casualties – 57 Muslims and 31 Buddhists.[1] An estimated 90,000 people were displaced by the violence.[12][13] About 2,528 houses were burned; of those, 1,336 belonged to Rohingyas and 1,192 belonged to Rakhines.[14]

Rohingya NGOs have accused the Burmese army and police of playing a role in targeting Rohingya through mass arrests and arbitrary violence[15] though an in-depth research by the International Crisis Group reported that members of both communities were grateful for the protection provided by the military.[16] While the government response was praised by the United States and European Union,[17][18] NGOs were more critical, citing discrimination of Rohingyas by the previous military government.[17] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and several human rights groups rejected the President Thein Sein's proposal to resettle the Rohingya abroad.[19][20]

Fighting broke out again in October, resulting in at least 80 deaths, the displacement of more than 20,000 people, and the burning of thousands of homes. Rohingyas are not allowed to leave their settlements, officially due to security concerns, and are the subject of a campaign of commercial boycott led by Buddhist monks.[21]

Contents

[hide]Background[edit]

Sectarian clashes occur sporadically in Rakhine State, often between the Buddhist Rakhine people who are majority in the southern part, and Rohingya Muslims who are majority in the north.[22] Before the riots, there were widespread and strongly held fears circulating among Buddhist Rakhines that they would soon become a minority in their ancestral state, and not just the northern part, which has long become a Muslim majority. Rohingyas migrated to Burma from Bengal, today's Bangladesh primarily before and during the period of British rule,[23][24][25]and to a lesser extent, after the Burmese independence in 1948 and Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.[22][22][26][27] Rakhines believed that many immigrants arrived even after the 1980s. The Burmese government classifies the Rohingya as "immigrants" to Burma, and thus not eligible for citizenship. Due to their lack of citizenship, they were previously subject to restrictions on government education, officially recognised marriages, and along with ethnic Rakhines, endured forced labour under the military government.[28][29]

On the evening of 28 May, a group of Muslim men robbed, raped and murdered an ethnic Rakhine woman, Ma Thida Htwe, near her village Tha Pri Chaung on 28 May 2012, when she was returning home from Kyauk Ni Maw Village of Rambree township.[30] The locals claim the culprits to have been Rohingya Muslims. The police arrested three suspects and sent them to Yanbye township jail.[31] On 3 June,[32] a mob attacked a bus in Taungup, apparently mistakenly believing those responsible for the murder were on board.[33] Ten Muslims were killed in the attack,[34] prompting protests by Burmese Muslims in the commercial capital, Yangon. The government responded by appointing a minister and a senior police chief to head an investigation committee. The committee was ordered to find out "cause and instigation of the incident" and to pursue legal action.[35] As of 2 July 30 people had been arrested over the killing of the Muslims.[36]

June riots[edit]

The June riots saw various attacks by Buddhist Rakhines and Rohingya Muslims on each other's communities, including destruction of property.[37]

8 June: Initial attacks[edit]

Despite increased security measures, at 3:50 pm 8 June, a large mob of Rakhine ignited several houses in Bohmu Village, Maungdaw Township where 80% of the population is Rohingya Muslims. Telephone lines were also damaged.[38] By the evening, Hmuu Zaw, a high-ranking officer, reported that the security forces were protecting 14 burnt villages in Maungdaw township. Around 5:30, the forces were authorised to use deadly force but they fired mostly warning shots according to local media.[38][39] Soon afterward, authorities declared that the situation in Maungdaw Township had been stabilised. However, three villages of southern Maungdaw were torched in early evening. At 9 o'clock, the government imposed curfew in Maungdaw, and forbidding any gathering of more than five persons in public area. An hour later, the rioters had a police outpost in Khayay Mying Village surrounded. The police fired warning shots to disperse them.[39] At 10 o'clock, armed forces had taken positions in Maungdaw. Five people had been confirmed killed as of 8 June.[40]

9 June: Riots spread[edit]

On the morning of 9 June, five army battalions arrived to reinforce the existing security forces. Government set up refugee camps for those whose houses had been burned. Government reports stated that Relief and Resettlement Ministry and Ministry of Defense had distributed 3.3 tons of supplies and 2 tons of clothes respectively.[41]

Despite increased security presence, the riots continued unabated. Security forces successfully prevented rioters' attempt to torch five quarters of Maungdaw. However, Rakhine villagers from Buthidaung Township (where 90 percent of people are Rohingya Muslims) arrived at refugee camps after their houses had been razed by Muslims. Soon after, soldiers took positions and anti-riot police patrolled in the township. The Muslim rioters marched to Sittwe and burned down three houses in Mingan quarter. An official report stated that at least 7 people had been killed, one hostel, 17 shops and over 494 houses had been destroyed as of 9 June.[41]

10 June: State of emergency[edit]

On 10 June, a state of emergency was declared across Rakhine.[22] According to state TV, the order was given in response to "unrest and terrorist attacks" and "intended to restore security and stability to the people immediately."[22] President Thein Sein added that further unrest could threaten the country's moves toward democracy.[42] It was the first time that the current government used the provision. It instigated martial law, giving the military administrative control of the region.[22]The move was criticised by Human Rights Watch, who accused the government of handing control over to a military which had historically brutalised people in the region.[42][43] Some ethnic Rakhine burned Rohingya houses in Bohmu village in retaliation.[44] Over five thousand people were residing at refugee camps by 10 June.[45] Many of the refugees fled to Sittwe to escape the rioting, overwhelming local officials.[42]

12–14 June[edit]

On 12 June, more buildings were set ablaze in Sittwe as many residents throughout Rakhine were relocated.[46] "Smoke is billowing from many directions and we are scared," said one ethnic Rakhine resident. "The government should send in more security forces to protect [our] communities."[43] An unnamed government official put the death toll at 25 to date.[43]

The number of casualties were officially revised to 21 on 13 June.[47] A top United Nations envoy visited the region affected by the riots. "We're here to observe and assess how we can continue to provide support to Rakhine [State]," said Ashok Nigam, UN humanitarian coordinator.[47] The envoy later remarked that army appeared to have restored order to the region.[13]

Meanwhile, Bangladeshi authorities continued to turn away refugees, denying another 140 people entry into Bangladesh. To date at least 15 boats and up to 1,500 total refugees had been turned away.[47] Dipu Moni, Foreign Minister of Bangladesh, said at a news conference in the capital, Dhaka, that Bangladesh did not have the capacity to accept refugees because the impoverished country’s resources already are strained.[48] The UN called on Bangladesh to reconsider.[49]

On 14 June, the situation appeared calm as casualty figures were updated to 29 deaths – 16 Muslim and 13 Buddhists according to Myanmar authorities.[13] The government also estimated 2,500 homes had been destroyed and 30,000 people displaced by the violence. Thirty-seven camps across Rakhine housed the refugees.[13] Opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi warned that violence would continue unless "the rule of law" was restored.[13]

15–28 June: Fatality figures update and arrest of UN workers[edit]

As of 28 June, casualty figures were updated to 80 deaths and estimated 90,000 people were displaced and taking refuge in temporary camps according to official reports.[50] Hundreds of Rohingyas fled across the border to Bangladesh, though many were forced back to Burma. Rohingyas who fled to Bangladesh also claimed that the Burmese army and police shot groups of villagers after they started the riot. They stated they feared to return to Burma when Bangladesh rejected them as refugees and asked them to go back home.[15][15] Despite the claims made by NGOs, an in-depth research by the International Crisis Group reported that members of both communities were grateful for protection provided by the military.[16]

The Government of Myanmar arrested 10 UN UNHCR workers and charged three with "stimulating" the riots.[51] António Guterres, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, visited Yangon and asked for the release of the UN workers which Myanmar's President Thein Sein said he would not allow but asked if the UN would help to resettle up to 1,000,000 Rohingya Muslims in either refugee camps in Bangladesh or some other country.[51] The UN rejected Thein Sein's proposal.[19]

October riots[edit]

Violence between Muslims and Buddhists broke out again in late October.[52][53] According to the Burmese government, more than 80 people were killed, more than 22,000 people were displaced, and more than 4,600 houses burnt.[4] The outburst of fighting brought the total number of displaced since the beginning of the conflict to 100,000.[4]

The violence began in the towns of Min Bya and Mrauk Oo by the Muslims, but spread across the state.[52] Though the majority of Rakhine state's Muslims are Rohingya, Muslims of all ethnicities were reported to be targets of the violence in retaliation.[5][6] Several Muslim groups announced that they would not be celebrating Eid al-Adha because they felt the government could not protect them.[53]

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon issued a statement on 26 October that "the vigilante attacks, targeted threats and extremist rhetoric must be stopped. If this is not done ... the reform and opening up process being currently pursued by the government is likely to be jeopardised."[52] US State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland called on the Burmese government to halt the violence and allow aid groups unrestricted access.[53] On 27 October, a spokesperson for Thein Sein acknowledged "incidents of whole villages and parts of the towns being burnt down in Rakhine state", after Human Rights Watch released a satellite image showing hundreds of Muslim buildings destroyed in Kyaukpyu on Ramree Island.[5] The United Nations reported on 28 October that 3,200 more displaced people had fled to refugee camps, with an estimated additional 2,500 still in transit.[54]

In early November, Doctors Without Borders reported that pamphlets and posters were being distributed in Rakhine State threatening aid workers who treated Muslims, causing almost all of its local staff to quit.[55]

Misleading photographs in the media[edit]

Alleged photographs of crimes against Muslims perpetrated by Buddhists in Rakhine State had been widely circulated during and after the riots. Some of the photos were taken from natural disasters, such as pictures of Tibetan Buddhist monks cremating earthquake victims from the 2010 Yushu earthquake, mislabeled as Burmese monks burning Muslims alive.[56][57]

Aftermath[edit]

Expulsion of Muslims from Sittwe[edit]

After the riots, most of the Muslims from Sittwe were temporarily removed by security forces into makeshift refugee camps well away from the city, towards Bangladesh. Only few hundred households were left in the ghetto-like Mingalar Ward where they are confined, officially due to security concerns.[58] Buddhists in Rakhine are calling for further internment and expulsion of Muslims who cannot prove three generations of legal residence - a large part of the nearly one million Muslims from the state.[59]

Rohingya diaspora[edit]

Around 140,000 people, the majority of them Rohingya, were displaced by two waves of violence between Buddhists and Muslims in Rakhine last year that left some 200 people dead. Thousands of Rohingya have fled Myanmar since then on overcrowded boats to Malaysia or further south, despite the dangers posed by rough seas. Hundreds are believed to have died at sea in 2013. In May, nearly 60 Rohingyas went missing after their boat sank after hitting rocks as a cyclone approached the bay.

In November, another boat carrying 70 Rohingyas fleeing sectarian violence capsized off the western coast of Myanmar. Only eight survivors have been found.[60]According to The Economist, later Burmese Buddhist mob violence against Muslims in such places as Meiktila, Okpho and Gyobingauk Township "follows on from, and is clearly inspired by, the massacres of Rohingya Muslims around Sittwe"[61] and "now seems to be spreading to other parts of Asia, too".[62]

Investigation[edit]

| This article needs to be updated. (December 2015) |

An investigation committee was formed on 28 March 2014 by the Burmese government to take action against the people involved in riots on 26 and 27 March 2014. The report on riots was to have been submitted by 7 April 2014 to the president.[63]

International events[edit]

On 5 April 2013, Muslim and Buddhist inmates at an immigration detention centre Indonesia rioted along the lines of the conflict in their home country leading to death of 8 Buddhists and 15 injuries of Rohingyas.[64][65] According to the testimonies of Rohingya witnesses, the reason that sparked the riot was because of sexual harassment against female Rohingya Muslim inmates by the Burmese Buddhist inmates.[66][67] Indonesian court jailed 14 Muslim Rohingya for nine months each in December. The sentence was lighter than the maximum penalty for violence resulting in death, which is 12 years. The men's lawyer said they would appeal for freedom because there was no real evidence shown during the trial.[68]

Reactions[edit]

Domestic[edit]

- National League for Democracy – The NLD appealed to the rioters to stop.[69]

- 88 Generation Students Group – 88 Generation Students leaders called the riots "acts of terrorism" and acts that have "nothing to do with Islam, Buddhism, nor any other religion."[70]

- All Myanmar Islam Association – All Myanmar Islam Association, the largest Islam association in Myanmar, condemned the "terrorizing and destruction of lives and property of innocent people", declaring that "the perpetrators must be held accountable by law."[71][72]

- Some local analysts believe the riots and conflict were instigated by the military, with the aim to embarrass Aung San Suu Kyi during her European tour, to reassert their own authority, or to divert attention from other conflicts involving ethnic minorities across the country.[73]

- In August 2012 President Thein Sein announced the establishment of a 27-member commission to investigate the violence. The commission would include members of different political parties and religious organisations.[74]

International[edit]

European Union – Earlier in 2012, the EU lifted some of its economic and political sanctions on Myanmar. As of 22 July, EU diplomats were monitoring the situation in the country and were in contact with its officials.[75]

European Union – Earlier in 2012, the EU lifted some of its economic and political sanctions on Myanmar. As of 22 July, EU diplomats were monitoring the situation in the country and were in contact with its officials.[75] Organisation of Islamic Cooperation – On 15 August, a meeting of the OIC condemned Myanmar authorities for violence against Rohingyas and the denial of the group's citizenship, and vowed to bring the issue to the United Nations General Assembly.[76] In October, the OIC had reached an agreement with the Burmese government to open an office in the country to help the Rohingyas; however, following Buddhist pressure,[77] the move was abandoned.[78]

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation – On 15 August, a meeting of the OIC condemned Myanmar authorities for violence against Rohingyas and the denial of the group's citizenship, and vowed to bring the issue to the United Nations General Assembly.[76] In October, the OIC had reached an agreement with the Burmese government to open an office in the country to help the Rohingyas; however, following Buddhist pressure,[77] the move was abandoned.[78] Bangladesh – Neighbouring Bangladesh increased border security in response to the riots. Numerous boat refugees were turned aside by the Border Guard.[33]

Bangladesh – Neighbouring Bangladesh increased border security in response to the riots. Numerous boat refugees were turned aside by the Border Guard.[33] Iran – Members of Iranian society[who?] condemned the attacks and called on other Muslim states to take a "firm stance" against the violence; protests also took place in Iran.[79]

Iran – Members of Iranian society[who?] condemned the attacks and called on other Muslim states to take a "firm stance" against the violence; protests also took place in Iran.[79] Pakistan – Foreign Ministry spokesman Moazzam Ali Khan said during a weekly news briefing: "We are concerned about the situation, but there are reports that things have improved there." He added that Pakistan hoped Burmese authorities would exercise necessary steps to bring the situation back to control.[80]Protests against the anti-Muslim riots were lodged by various political parties and organisations in Pakistan, who called for the government, United Nations, OICand human rights organisations to take notice of the killings and hold Myanmar accountable.[81][82]

Pakistan – Foreign Ministry spokesman Moazzam Ali Khan said during a weekly news briefing: "We are concerned about the situation, but there are reports that things have improved there." He added that Pakistan hoped Burmese authorities would exercise necessary steps to bring the situation back to control.[80]Protests against the anti-Muslim riots were lodged by various political parties and organisations in Pakistan, who called for the government, United Nations, OICand human rights organisations to take notice of the killings and hold Myanmar accountable.[81][82] Saudi Arabia – The King Abdullah ordered $50 million of aid sent to the Rohingyas, in Saudi Arabia's capacity as a "guardian of global Muslim interests".[83]Council of Ministers of Saudi Arabia says that it "condemns the ethnic cleansing campaign and brutal attacks against Myanmar's Muslim Rohingya citizens" and it urged the international community to protect "Muslims in Myanmar".[84]

Saudi Arabia – The King Abdullah ordered $50 million of aid sent to the Rohingyas, in Saudi Arabia's capacity as a "guardian of global Muslim interests".[83]Council of Ministers of Saudi Arabia says that it "condemns the ethnic cleansing campaign and brutal attacks against Myanmar's Muslim Rohingya citizens" and it urged the international community to protect "Muslims in Myanmar".[84] United Kingdom – Foreign Minister Jeremy Browne told reporters that he was 'deeply concerned' by the situation and that the UK and other countries would continue to watch developments closely.[85]

United Kingdom – Foreign Minister Jeremy Browne told reporters that he was 'deeply concerned' by the situation and that the UK and other countries would continue to watch developments closely.[85] United States – Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for "all parties to exercise restraint" and added that "the United States continues to be deeply concerned" about the situation.[86][87]

United States – Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for "all parties to exercise restraint" and added that "the United States continues to be deeply concerned" about the situation.[86][87] Tibet The 14th Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet in exile, wrote a letter in August 2012 to Aung San Suu Kyi, where he said that he was “deeply saddened” and remains “very concerned” with the violence inflicted on the Muslims in Burma.[88] In April 2013, he openly criticised Buddhist monks' attacks on Muslims in Myanmar saying "Buddha always teaches us about forgiveness, tolerance, compassion. If from one corner of your mind, some emotion makes you want to hit, or want to kill, then please remember Buddha's faith. We are followers of Buddha." He said that "All problems must be solved through dialogue, through talk. The use of violence is outdated, and never solves problems."[89] In May 2013, while visiting Maryland, he said "Really, killing people in the name of religion is unthinkable, very sad."[90]

Tibet The 14th Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet in exile, wrote a letter in August 2012 to Aung San Suu Kyi, where he said that he was “deeply saddened” and remains “very concerned” with the violence inflicted on the Muslims in Burma.[88] In April 2013, he openly criticised Buddhist monks' attacks on Muslims in Myanmar saying "Buddha always teaches us about forgiveness, tolerance, compassion. If from one corner of your mind, some emotion makes you want to hit, or want to kill, then please remember Buddha's faith. We are followers of Buddha." He said that "All problems must be solved through dialogue, through talk. The use of violence is outdated, and never solves problems."[89] In May 2013, while visiting Maryland, he said "Really, killing people in the name of religion is unthinkable, very sad."[90]

See also[edit]

- Chittagong Hill Tracts conflict

- Persecution of Buddhists#Bangladesh

- Genocide of indigenous peoples#Bangladesh

- Wartime sexual violence#Bangladesh - Chittagong Hill Tracts

- Chakma people

- Jumma people

- 969 Movement

- South Thailand insurgency

- 2012 Ramu violence

- 2012 Assam violence

- 2013 Burma anti-Muslim riots

- 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis

- Buddhism and violence

- Persecution of Muslims in Burma

- Rohingya conflict in Western Burma

- Criticism of Buddhism#War and violence.

Rohingya insurgency in Western Myanmar

(Redirected from Rohingya conflict in Western Burma)

| Rohingya insurgency in Western Myanmar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Internal conflict in Myanmar | |||||||

|

Rohingya population in Rakhine State (Arakan)

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Former combatants:

|

ARSA (since 2016)

Former combatants:

(1947–1961)

Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

(Rakhine Chief of Police)[5]

Former commanders:

(1992–2011)

|

Former commanders:

(1947–1961)

(1947–1961)

(1961–1974)

Muhammad Jafar Habib (1972–1982)

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Rohingya National Army(1998–2001)[2][9] | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

Previous totals:

1,100 (1947–1950)[10]

|

~500 (2016)[8]

Previous totals:

2,000–5,000 (1947–1950)[10]

2,000 (1952)[10]

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

44 security personnel killed[a]

| |||||||

2012–2017:

1,400+ killed in total[b]

30,000 internally displaced[16]

168,000 fled abroad[17]

| |||||||

The Rohingya insurgency in Western Myanmar is an ongoing insurgency in northern Rakhine State, Myanmar (formerly known as Arakan, Burma), waged by insurgents belonging to the Rohingya ethnic minority. Most clashes have occurred in the Maungdaw District, which borders Bangladesh.

From 1947 to 1961, local mujahideen fought government forces in an attempt to have the mostly Rohingya populated Mayu peninsula in northern Rakhine State secede from Myanmar, so it could be annexed by East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh).[25] During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the mujahideen lost most of its momentum and support, resulting in most of them surrendering to government forces.[26][27]

In the 1970s Rohingya Islamist movements began to emerge from remnants of the mujahideen, and the fighting culminated with the Burmese government launching a massive military operation named Operation King Dragon in 1978.[28] In the 1990s, the well-armed Rohingya Solidarity Organisation was the main perpetrator of attacks on Burmese authorities near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border.[29]

In October 2016, clashes erupted on the Myanmar-Bangladesh border between government security forces and a new insurgent group, Harakah al-Yaqin, resulting in the deaths of at least 40 people (excluding civilians).[30][31][32] It was the first major resurgence of the conflict since 2001.[2] In November 2016, violence erupted again, bringing the death toll to 134.[11]

During the early hours of 25 August 2017, up to 150 insurgents launched coordinated attacks on 24 police posts and the 552nd Light Infantry Battalion army base in Rakhine State, leaving 71 dead (12 security personnel and 59 insurgents). It was the first major attack by Rohingya insurgents since November 2016.[18][19][33]

Contents

[hide]Background[edit]

The Rohingya people are an ethnic minority that mainly live in the northern region of Rakhine State, Myanmar, and have been described as one of the world's most persecuted minorities.[34][35][36] They describe themselves as descendants of Arab traders who settled in the region many generations ago.[34] Some scholars have stated that they have been present in the region since the 15th century.[37] However, they have been denied citizenship by the government of Myanmar, which sees them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.[34] In modern times, the persecution of Rohingyas in Myanmar dates back to the 1970s.[38] Since then, Rohingya people have regularly been made the target of persecution by the government and nationalist Buddhists.[39]

Mujahideen separatist movements (1947–1960s)[edit]

Early separatist insurgency[edit]

In May 1946, Muslim leaders from Arakan, Burma (present-day Rakhine State, Myanmar) met with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, and asked for the formal annexation of two townships in the Mayu region, Buthidaung and Maungdaw, by East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh). Two months later, the North Arakan Muslim League was founded in Akyab (present-day Sittwe, capital of Rakhine State), which also asked Jinnah to annex the region.[40] Jinnah refused, saying that he could not interfere with Burma's internal matters. After Jinnah's refusal, proposals were made by Muslims in Arakan to the newly formed post-independence government of Burma, asking for the concession of the two townships to Pakistan. The proposals were rejected by the Burmese parliament.[41]

Local mujahideen were subsequently formed against the Burmese government,[42] and began targeting government soldiers stationed in the area. Led by Mir Kassem, the newly formed mujahideen movement began gaining territory, driving out local Rakhine communities from their villages, some of whom fled to East Pakistan.[43]

In November 1948, martial law was declared in the region, and the 5th Battalion of the Burma Rifles and the 2nd Chin Battalion were sent to liberate the area. By June 1949, the Burmese government's control over the region was reduced to the city of Akyab, whilst the mujahideen had possession of nearly all of northern Arakan. After several months of fighting, Burmese forces were able to push the mujahideen back into the jungles of the Mayu region, near the country's border with East Pakistan.

In 1950, the Pakistani government warned its counterparts in Burma about their treatment of Muslims in Arakan. Burmese Prime Minister U Nu immediately sent a Muslim diplomat, Pe Khin, to negotiate a memorandum of understanding, so that Pakistan would cease sending aid to the mujahideen. In 1954, Kassem was arrested by Pakistani authorities, and many of his followers surrendered to the government.[3]

The post-independence government accused the mujahideen of encouraging the illegal immigration of thousands of Bengalis from East Pakistan into Arakan during their rule of the area, a claim that has been highly disputed over the decades, as it brings into question the legitimacy of the Rohingya as an ethnic group of Myanmar.[26]

Military operations against the mujahideen[edit]

Between 1950 and 1954, the Burma Army launched several military operations against the remaining mujahideen in northern Arakan.[44] The first military operation was launched in March 1950, followed by a second named Operation Mayu in October 1952. Several mujahideen leaders agreed to disarm and surrender to government forces following the successful operations.[40]

In the latter half of 1954, the mujahideen again began to carry out attacks on local authorities and military units stationed around Maungdaw, Buthidaung and Rathedaung. In protest, hundreds of Rakhine Buddhist monksbegan hunger strikes in Rangoon (present-day Yangon),[26] and in response the government launched Operation Monsoon in October 1954.[40] The Tatmadaw managed to capture the main strongholds of the mujahideen and managed to kill several of their leaders. The operation successfully reduced the mujahideen's influence and support in the region.[10]

Decline and fall of the mujahideen[edit]

In 1957, 150 mujahideen, led by Shore Maluk and Zurah, surrendered to government forces. On 7 November 1957, 214 additional mujahideen under the leadership of al-Rashid disarmed and surrendered to government forces.[27]

In the beginning of the 1960s, the mujahideen began to lose its momentum after the governments of Myanmar (Burma) and Pakistan (which controlled Bangladesh at the time) began negotiating on how to deal with the insurgents at their border. On 4 July 1961, 290 mujahideen in southern Maungdaw Township surrendered their arms in front of Brigadier-General Aung Gyi, the then Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Burmese Army.[45] On 15 November 1961, the few remaining mujahideen surrendered to Aung Gyi in the eastern region of Buthidaung.[26]

A few dozen insurgents remained under the command of Zaffar Kawal, another group of 40 insurgents were led by Abdul Latif, and a mujahideen faction of 80 insurgents were led by Annul Jauli. All these groups lacked local support and a unifying ideology, which lead them to become rice smugglers around the end of the 1960s.[27]

Rohingya Islamist movements (1972–2001)[edit]

Islamist movements in the 1970s and 1980s[edit]

On 15 July 1972, former mujahideen leader Zaffar Kawal founded the Rohingya Liberation Party (RLP), after mobilising various former mujahideen factions under his command. Zaffar appointed himself Chairman of the party, Abdul Latif as Vice Chairman and Minister of Military Affairs, and Muhammad Jafar Habib as the Secretary General, a graduate from Rangoon University. Their strength increased from 200 fighters in the beginning to 500 by 1974. The RLP was largely based in the jungles of Buthidaung, and were armed with weapons smuggled from Bangladesh. After a massive military operation by the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) in July 1974, Zaffar and most of his men fled across the border into Bangladesh.[27][46]

In 1974, Muhammad Jafar Habib, the former Secretary of the RLP, founded the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF), after the failure and dissolution of the RLP. The RPF had around 70 fighters,[27][2] Habib as self-appointed Chairman, Nurul Islam, a Yangon-educated lawyer, as Vice-Chairman, and Muhammad Yunus, a medical doctor, as Secretary General.[27]

In March 1978, government forces launched a massive military operation named Operation King Dragon in northern Arakan (Rakhine State), with the focus of expelling Rohingya insurgents in the area.[28] As the operation extended farther northwest, hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas crossed the border seeking refuge in Bangladesh.[2][47][48]

In 1982, more radical elements broke away from the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF), and formed the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO).[1][2] It was led by Muhammad Yunus, the former Secretary General of the RPF. The RSO became the most influential and extreme faction amongst Rohingya insurgent groups; by basing itself on religious grounds it gained support from various Islamist groups, such as Jamaat-e-Islami in Bangladesh and Pakistan, Hizb-e-Islami in Afghanistan, Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM) in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, and Angkatan Belia Islam sa-Malaysia (ABIM) and the Islamic Youth Organisation of Malaysia in Malaysia.[2][48]

On 15 October 1982, the Burmese Citizenship Law was introduced, and with the exception of the Kaman people, most Muslims in the country were denied an ethnic minority classification, and thus were denied Burmese citizenship.[49]

A more moderate Rohingya insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front (ARIF), was founded in 1986 by Nurul Islam, the former Vice-Chairman of the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF), after uniting remnants of the old RPF and a handful of defectors from the RSO.[2]

Military expansions in the 1990s[edit]

In the early 1990s, the military camps of the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO) were located in the Cox's Bazar District in southern Bangladesh. RSO possessed a significant arsenal of light machine-guns, AK-47 assault rifles, RPG-2 rocket launchers, claymore mines and explosives, according to a field report conducted by correspondent Bertil Lintner in 1991.[29] The Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front (ARIF) was mostly armed with British manufactured 9mm Sterling L2A3 sub-machine guns, M-16 assault rifles and .303 rifles.[29]

The military expansion of the RSO resulted in the government of Myanmar launching a massive counter-offensive to expel RSO insurgents along the Bangladesh-Myanmar border. In December 1991, Tatmadaw soldiers crossed the border and accidentally attacked a Bangladeshi military outpost, causing a strain in Bangladeshi-Myanmar relations. By April 1992, more than 250,000 Rohingya civilians had been forced out of northern Rakhine State (Arakan) as a result of the increased military operations in the area.[2]

In April 1994, around 120 RSO insurgents entered Maungdaw Township in Myanmar by crossing the Naf River which marks the border between Bangladesh and Myanmar. On 28 April 1994, nine out of twelve bombs planted in different areas in Maungdaw by RSO insurgents exploded, damaging a fire engine and a few buildings, and seriously wounding four civilians.[50]

On 28 October 1998, the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation merged with the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front and formed the Arakan Rohingya National Organisation(ARNO), operating in-exile in Cox's Bazaar.[2] The Rohingya National Army (RNA) was established as its armed wing.

One of the several dozen videotapes obtained by CNN from Al-Qaeda's archives in Afghanistan in August 2002 allegedly showed fighters from Myanmar training in Afghanistan.[51] Other videotapes were marked with "Myanmar" in Arabic, and it was assumed that the footage was shot in Myanmar, though this has not been validated.[2][48] According to intelligence sources in Asia,[who?] Rohingya recruits in the RSO were paid a 30,000 Bangladeshi taka ($525 USD) enlistment reward, and a salary of 10,000 taka ($175) per month. Families of fighters who were killed in action were offered 100,000 taka ($1,750) in compensation, a promise which lured many young Rohingya men, who were mostly very poor, to travel to Pakistan, where they would train and then perform suicide attacks in Afghanistan.[2][48]

The Islamic extremist organisations Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami[52] and Harkat-ul-Ansar[53] also claimed to have branches in Myanmar.

2016–17 clashes[edit]

On 9 October 2016, hundreds of unidentified insurgents attacked three Burmese border posts along Myanmar's border with Bangladesh.[54] According to government officials in the mainly Rohingya border town of Maungdaw, the attackers brandished knives, machetes and homemade slingshots that fired metal bolts. Several dozen firearms and boxes of ammunition were looted by the attackers from the border posts. The attack resulted in the deaths of nine border officers.[31] On 11 October 2016, four Burmese Army soldiers were killed on the third day of fighting.[32] Following the attacks, reports emerged of several human rights violations allegedly perpetrated by Burmese security forces in their crackdown on suspected Rohingya insurgents.[55]

Government officials in Rakhine State originally blamed the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation (RSO), an Islamist insurgent group mainly active in the 1980s and 1990s, for the attacks;[56] however, on 17 October 2016, a group calling itself Harakah al-Yaqin (Faith Movement) released a video on several social media sites claiming responsibility.[57] In the following days, six other groups released statements, all citing the same leader.[58]

On 15 November 2016, the Burmese Army announced that 69 Rohingya insurgents and 17 security forces (10 policemen, 7 soldiers) had been killed in recent clashes in northern Rakhine State, bringing the death toll to 134 (102 insurgents and 32 security forces). It was also announced that 234 people suspected of being connected to the attack were arrested.[11]

On 30 December 2016, nearly two dozen prominent human rights activists, including Malala Yousafzai, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Richard Branson, called on the United Nations Security Council to intervene and end the "ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity" being perpetrated in northern Rakhine State.[59]

In March 2017, a police document obtained by Reuters listed 423 Rohingyas detained by the police since 9 October 2016, 13 of whom were children, the youngest being ten years old. Two police captains in Maungdaw verified the document and justified the arrests, with one of them saying, "We the police have to arrest those who collaborated with the attackers, children or not, but the court will decide if they are guilty; we are not the ones who decide." Myanmar police also claimed that the children had confessed to their alleged crimes during interrogations, and that they were not beaten or pressured during questioning. The average age of those detained is 34, the youngest is 10, and the oldest is 75.[14][15]

On 25 August 2017, the government announced that 71 people (one soldier, one immigration officer, 10 policemen and 59 insurgents) had been killed overnight during coordinated attacks by up to 150 insurgents on 26 police posts and the 552nd Light Infantry Battalion army base in Rakhine State.[18][19][33]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

Rakhine people

| This article may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (December 2016) |

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (Total: 3,361,000 (2010 est.)) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,346,000 | |

| 207,000 | |

| 50,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Arakanese, Burmese | |

| Religion | |

| Theravada Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bamar, Chakma | |

The Rakhine (Burmese: ရခိုင်လူမျိုး, Rakhine pronunciation [ɹəkʰàiɴ lùmjó]; Burmese pronunciation: [jəkʰàiɴ lùmjó]; formerly Arakanese), are an ethnic group in Myanmar (Burma) forming the majority along the coastal region of present-day Rakhine State (formerly officially called Arakan). They possibly constitute 5.53% or more of Myanmar's total population, but no accurate census figures exist. Arakanese people also live in the southeastern parts of Bangladesh, especially in Chittagong and Barisal Divisions. A group of Arakanese descendants, living in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh at least since the 16th century, are known as the Marma people or Mog people. These Arakanese descendants have been living in that area since the Arakanese kingdom's control of the Chittagong region.[citation needed]

Arakanese descendants spread as far north as Tripura state in India, where their presence dates back to the ascent of the Arakanese kingdom when Tripura was ruled by Arakanese kings. In northeast India, these Arakanese people are referred to as the Mog, while in Indian history, the Marma (the ethnic Arakanese descendants in Bangladesh) and other Arakanese people are referred to as the Magh people.[citation needed]

Contents

[hide]Culture[edit]

The Arakanese are predominantly Theravada Buddhists and are one of the four main Buddhist ethnic groups of Burma (the others being the Bamar, Shan and Mon people). They claim to be one of the first groups to become followers of Gautama Buddha in Southeast Asia. The Arakanese culture is similar to the dominant Burmese culture but with more Indian influence, likely due to its geographical isolation from the Burmese mainland divided by the Arakan Mountains and its closer proximity to South Asia subcontinent. Traces of Indian influence remain in many aspects of Arakanese culture, including its literature, music, and cuisine.

Language[edit]

The Arakanese language is closely related to and generally mutually intelligible with Burmese. Arakanese notably retains an /r/ sound that has become /j/ in Burmese. The modern Arakanese script is essentially the same as standard Burmese. Formerly, the Rakhawunna script, found in stone inscriptions in the Vesali (Wethali) era, was used to write in Arakan.[1]

History[edit]

Dhanyawadi[edit]

Ancient Dhanyawadi lies west of the mountain ridge between the Kaladan and Le-mro rivers. Its city walls were made of brick, and form an irregular circle with a perimeter of about 9.6 km, enclosing an area of about 4.42 square km. Beyond the walls, the remains of a wide moat, now silted over and covered by paddy fields, are still visible in places. The remains of brick fortifications can be seen along the hilly ridge which provided protection from the west. Within the city, a similar wall and moat enclose the palace site, which has an area of 0.26 square km, and another wall surrounds the palace itself. From aerial photographs we can discern Dhanyawad I's irrigation channels and storage tanks, centred at the palace site.[citation needed]

| Macroperiod | Period | Start year | End year | Ruler | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhanyavadi | The First Dhanyawadi | BC 3525 | BC 1489 | King Marayu | |

| The Second Dhanyawadi | BC 2483 | BC 580 | King Kanrazagree | ||

| The Third Dhanyawadi | BC 580 | AD 326 | King Chandra Suriya | Gautama Buddha, Himself, visited Dhanyawadi and the Great Image of Mahamuni was cast, and Buddhism began professing in Rakhine. Currency system by coinage is said to have been introduced in Rakhine economy. | |

| Vesali – Lemro | Vesali Kyauk Hlayga | AD 327 | AD 794 | King Dvan Chandra | |

| Sambawak | AD 794 | AD 818 | Prince Nga Tong Mong (Saw Shwe Lu) | ||

| Lemro | AD 818 | AD 1430 | King Nga Tone Mun | This period was the highest civilisation in the Bay and highly prosperous with busy international trade with the West. Pyinsa, Purain, Taung Ngu and Narinsara, Laungkrat cities flourished. Gold and silver coinage was used in trade relation in Rakhine in this period. | |

| First Golden Mrauk-U | AD 1430 | AD 1530 | King Mun Saw Mwan | ||

| Second Golden Mrauk-U | AD 1530 | AD 1638 | Solidified by King Mun Bun (Mun Ba Gri) | Rakhine reached at the zenith of the national unity and of the time of most powerful in the Bay in this period. | |

| Third Golden Mrauk-U Period | AD 1668 | AD 1784 | King Mahathamada Raza |

Mrauk-U[edit]

Mrauk-U, the last kingdom of independent Arakan founded by King Mong Saw Mon in 1430, has become the principal seat of Buddhism, has reaching at zenith of the golden age. Mrauk-U was divided into three periods: the earliest period (1430–1530), the middle period (1531–1638), and the last period (1638–1784). In Arakan antiquities at the Mrauk-U seems to give rational evidence as to where Buddhism was settled down. The golden days of Mrauk U city, those of 16th and 17th centuries, were contemporary to the days of Tudor kings, the Moghuls, the Ayuthiya kings and Ava (Inwa), Taungoo and Hanthawaddy kings of Myanmar. Mrauk U was cosmopolitan city, fortified by a 30-kilometer long fortification and an intricate net of moats and canals. At the centre of the city was the Royal Place, looming high over the surrounding area like an Asian Acropolis. Waterways formed by canals and creeks earned the fame of distinct resemblance to Venice. Mrauk U offers some of the richest archaeological sites in South-East Asia.

These include stone inscriptions, Buddha images, the Buddha's foot-prints and the great pagoda itself which, stripped its later-constructed top, would be of the same design as the Gupta style of ancient India. In the city of golden Mrauk-U there are scattering innumerable temples and pagodas which preserved as places, thereby exerting a great influence on spiritual life of the people.[citation needed]

Historical artefacts[edit]

The 243 Rakhine kings ruled Arakan for a long period of 5108 years. The oldest artefact, stone image of Fat Monk inscribed "Saccakaparibajaka Jina" in Brahmi script inscription comes to the date of first century AD.

An ancient stone inscription in Nagari character was discovered by renowned Archaeologist Dr. Forchhammer. Known as Salagiri, this hill was where the great teacher came to Rakhine some two thousand five hundred years ago. Somewhere from eastern part of this hill, a stone image in Dhamma-cakra-mudra now kept in Mrauk-U museum, was found earlier in 1923. This relief sculpture found on the Salagiri Hill represents Hindu Bengali King Chandra Suriya belongs to 4th century AD; five more red sandstone slabs with the carving were found close by the south of this Salagiri Hill in 1986. They are the same type as the single slab found earlier in 1923. These carving slabs of Bhumispara-mudra, Kararuna-mudra, Dhammacakra-mudara, and Mmahaparinibbana-mudra represent the life of Buddha.

These sculptures provide earliest evident about the advent of Buddhism into Rakhine; during the lifetime of the Buddha and these discoveries were therefore assumed as the figures of King Chandra Suriya of Dyanawadi, who dedicated the Great Maha Muni Image. These archaeological findings have been studied by eminent scholars and conclusion is that the Maha Muni was made during the king Sanda Suriya era.

The founder of Vesali city, King Dvan Chandra carved Vesali Paragri Buddha-image in 327 A.D and set a dedicatory inscription in Pali verse

That Buddha-image is carved out by a single block and the earliest image of Vesali.

The meaning of Ye Dhamma Hetu verse is as follow.

The verse, which is considered as the essence of Theravada spirit, bears testimony to the fact that Buddhism flourished to an utmost degree in Vesali. The relationship of Vesali with foreign countries especially Ceylon would be established for Buddhism.

The stone inscriptions are of Sanskrit in Brahma script, Pali, Rakhine, Pyu languages. Anandachandra Inscriptions date back to 729 AD originally from Vesali now preserved at Shitethaung indicates adequate evidence for the earliest foundation of Buddhism. Dr. E. H. Johnston's analysis reveals a list of kings which he considered reliable beginning from Chandra dynasty. The western face inscription has 72 lines of text recorded in 51 verses describing the Anandachandra's ancestral rulers. Each face recorded the name and ruling period of each king who were believed to have ruled over the land before Anandachandra. Archaeology has shown that the establishment of so many stone pagodas and inscriptions which have been totally neglected for centuries in different part of Rakhine speak of popular favoured by Buddhism.

The cubic stone inscriptions record the peace making between the governor of Thandaway (Sandoway) Mong Khari (1433–1459) and Razadhiraj the Mon Emperor in Rakhine inscription. This was found from a garrison hill at the oldest site of Parein. A stone slab with the alleged figure of the Hindu Bengali King Chandra Suriya bore testimony to the Salagiri tradition, depicting of the advent of the Teacher to Dyanyawaddy.

Convention of the Buddhist Council in Rakhine[edit]

The crowning event in the history of Rakhine was the Convention of the Buddhist Council at the top of golden hill of Vesali under the royal patronage of King Dhammawizaya in 638 AD through joint effort of two countries, Rakhine and Ceylon. This momentous triumph of the great council was participated by one thousand monks from Ceylon and one thousand monks from Rakhine kingdom. As a fitting celebration of the occasion, the lavish construction of pagodas, statues and monasteries were undertaken for the purpose of inscribing the Tripitaka. After Vesali, Pyinsa was found by Lemro dynasty in 818 AD; the great king of dynasty (AD 818–1430) was King Mim-Yin-Phru, who turned his attention towards the development of Buddhism, and in 847 AD he convened the second Buddhist council in Rakhine attended by 800 Arahants. Rakhine chronicles report that therein the Tripitaka and Atthakatha were inscribed on the golden plate and enshrined. Never has there been impediment in the practice of Theravada Buddhist faith since it has been introduced in Rakhine. The copious findings of inscription Ye Dhamma verse were practical evidence that Theravada was dominant faith if epigraphic and archaeological sources were to be believed. The Royal patronage has always been significant factor contribution to stability and progress of the religion in Rakhine.

Architecture[edit]

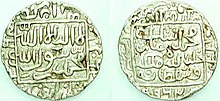

Arakanese chronicle records that more than six million shrines and pagodas flourished in Mrauk-U. In fact, they formed the pride of golden Mrauk-U. Dr. Forchhammer in his book entitled "Arakan", "in durability, architectural skill, and ornamentation the Mrauk-U temples far surpass those on the banks of Arrawaddy". Buddhist arts both in the field of architecture and Buddha-image constructions are on the same line of flourishing. An illustrative example of this fact can be seen in the temple of Chitthaung pagoda and colossal Dukekanthein temple. Gold and silver coins serve as the priceless heritage of the Mrauk-U period. The tradition of coin-making was handed down from the Vesali kings who started minting coins around the fifth century. The coins so far found are of one denomination only. Inscribed on the coins are the title of the ruling king and his year of coronation; coins before 1638 had Rakhine inscriptions on one side and Persian and Nagari inscriptions on the other. The inclusion of the foreign inscriptions was meant for the easy acceptance by the neighbouring countries and the Arab traders. Twenty-three types of silver coins and three types of gold coins have so far been found. All the kings who ascended the throne issued coins. City walls, gates, settlements, monastery sites, fortresses, garrisons and moats are the other priceless heritages left to the safe keeping of today's Rakhine people. Stone rubbles of proud mansions of that period are also priceless reminders of Rakhine glory.

It is no wonder that Mrauk U is properly known as the "Land of Pagodas" and Europeans remarked Mrauk U as "The Golden City". The Rakhine of those days were proud of Mrauk U. They were entirely satisfied to be the inhabitants of Mrauk U. The history shows what happened in the city in early times.

Foreign invasion[edit]

The country had been invaded several times, by the Mongols, Mon, Bamar and Portuguese and finally the Bamar in 1784 when the armies led by the Crown Prince, son of King Bodawpaya, of the Konbaung dynasty of Burma marched across the western Yoma and annexed Rakhine. The religious relics of the kingdom were stolen from Rakhine, most notably the Mahamuni Buddha image, and taken into central Burma where they remain today. The people of Rakhine resisted the conquest of the kingdom for decades after. Fighting with the Rakhine resistance, initially led by Nga Than Dè and finally by Chin Byan in border areas, created problems between British India and Burma. The year 1826 saw the defeat of the Bamar in the First Anglo-Burmese War and Rakhine was ceded to Britain under the Treaty of Yandabo. Sittwe (Akyab) was then designated the new capital of Rakhine. In 1852, Rakhine was merged into Lower Burma as a territorial division.

Independence movement[edit]

Rakhine was the centre of multiple insurgencies which fought against British rule, notably led by the monks U Ottama and U Seinda.

During the Second World War, Rakhine was given autonomy under the Japanese occupation of Burma and was even granted its own army known as the Arakan Defense Force. The Arakan Defense Force went over to the allies and turned against the Japanese in early 1945.

After the Union of Burma independence[edit]

In 1948, Rakhine became a division within the Union of Burma. In 1974, the Ne Win government's new constitution granted Rakhine Division "state" status but the gesture was largely seen as meaningless since the military junta held all power in the country and in Rakhine. Present-day Rakhine are mainly living in Rakhine State, some parts of Ayeyarwady Division and Yangon Division of Burma. And also few amount of Rakhine are living in southern part of Bangladesh and India.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Vesali Coins in Sittwe and Mrauk-U Archaeological Museum; The Ananda Chandra inscriptions (729 A.D), at Shit Thaung Temple-Mrauk U; Some Sanskrit Inscriptions of Arakan, by E. H. Johnston; Pamela Gutman (2001) Burma's Lost Kingdoms: splendours of Arakan. Bangkok: Orchid Press; Ancient Arakan, by Pamela Gutman; Arakan Coins, by U San Tha Aung; The Buddhist Art of Ancient Arakan, by U San Tha Aung.

Bibliography[edit]

- Charney, Michael W. (1999). 'Where Jambudipa and Islamdom Converged: Religious Change and the Emergence of Buddhist Communalism in Early Modern Arakan, 15th–19th Centuries.' PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan.

- Charney, Michael (2005). "Buddhism in Arakan:Theories and Historiography of the Religious Basis of Ethnonyms". "Arakan History Conference" [Bangkok]. Chulalongkorn University. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- Leider, Jacques P. (2004). 'Le Royaume d'Arakan, Birmanie. Son histoire politique entre le début du XVe et la fin du XVIIe siècle,' Paris, EFEO.

- Loeffner, L. G. (1976). "Historical Phonology of Burmese and Arakanese Finals." Ninth International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Copenhagen. 22–24 Oct. 1976.

Bengalis

| বাঙালি | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 300 million[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Bengal | |

| 163,187,000[3] | |

| 83,369,769[4] | |

| 2,000,000[5][6][7][8] | |

| 1,815,000[9] | |

| 1,089,917[10] | |

| 500,000[11] | |

| 451,000[12] | |

| 347,000[13] | |

| 280,000[14] | |

| 257,740[15][16][a] | |

| 200,000[17] | |

| 155,000[18] | |

| 113,000[19] | |

| 97,115[20] | |

| 93,000[21] | |

| 70,000[22] | |

| 69,490[23] | |

| 54,566[24] | |

| 34,000[25] | |

| 30,500[26] | |

| 23,500[27] | |

| 23,000[28] | |

| 13,000[29] | |

| Languages | |

| Bengali | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan peoples | |

| This article is part of a series on the |

|

|

|---|

|

| Language and Literature |

| Regions |

| Subgroup |

| Arts and Tradition |

| Symbols |

The Bengalis (বাঙালি Bangali), also rendered as the Bengali people, Bangalis and Bangalees,[33] are an Indo-Aryanethnic group native to the region of Bengal in South Asia, which is presently-divided between Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. They speak the Bengali language, one of the most easterly representatives of the Indo-European language family.

Bengalis are the third largest ethnic group in the world after Han Chinese and Arabs.[34] Apart from Bangladesh and West Bengal, Bengali-majority populations also reside in India's Tripura state, the Barak Valley in Assam state, and the union territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The global Bengali diaspora has well-established communities in Pakistan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, the Middle East, Japan, Singapore, and Italy.

They have four major religious subgroups: Bengali Muslims, Bengali Hindus, Bengali Christians and Bengali Buddhists.

Contents

[hide]History

Ancient history

Archaeologists have discovered remnants of a 4,000-year-old Chalcolithic civilisation in the greater Bengal region, and believe the finds are one of the earliest signs of settlement in the region.[35] However, evidence of much older Palaeolithic human habitations were found in the form of a stone implement and a hand axe in Rangamati and Fenidistricts of Bangladesh.[36] The origin of the word Bangla ~ Bengal is unknown, though it is believed to be derived from a tribe called Bang that settled in the area around the year 1000 BCE.[37]

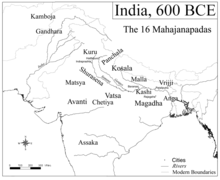

Kingdoms of Pundra and Vanga were formed in Bengal and were first described in the Atharvaveda around 1000 BCE as well as in Hindu epic Mahabharata. Anga and later Magadha expanded to include most of the Bihar and Bengalregions. It was one of the four main kingdoms of India at the time of Buddha and was one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas. Under the Maurya Empire founded by Chandragupta Maurya, Magadha extended over nearly all of South Asia, including parts of Balochistan and Afghanistan, reaching its greatest extent under the Buddhist emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BCE.

One of the earliest foreign references to Bengal is the mention of a land ruled by the king Xandrammes named Gangaridai by the Greeks around 100 BCE. The word is speculated to have come from Gangahrd ('Land with the Ganges in its heart') in reference to an area in Bengal.[38] Later from the 3rd to the 6th centuries CE, the kingdom of Magadha served as the seat of the Gupta Empire.

Middle Ages

One of the first recorded independent kings of Bengal was Shashanka, reigning around the early 7th century.[39] After a period of anarchy, Gopala came to power in 750. He founded the Bengali Buddhist Pala Empire which ruled the region for four hundred years, and expanded across much of Southern Asia: from Assam in the northeast, to Kabul in the west, and to Andhra Pradesh in the south. Atisha was a renowned Bengali Buddhist teacher who was instrumental in the revival of Buddhism in Tibet and also held the position of Abbot at the Vikramshila university. Tilopa was also from Bengal region.

The Pala dynasty was later followed by a shorter reign of the Hindu Sena Empire. Islam was introduced to Bengal in the twelfth century by Sufi missionaries. Subsequent Muslim conquests helped spread Islam throughout the region.[40]Bakhtiar Khilji, a Turkic general of the Slave dynasty of Delhi Sultanate, defeated Lakshman Sen of the Sena dynasty and conquered large parts of Bengal. Consequently, the region was ruled by dynasties of sultans and feudal lords under the Bengal Sultanate for the next few hundred years. Islam was introduced to the Sylhet region by the Muslim saint Shah Jalal in the early 14th century. Mughal general Man Singh conquered parts of Bengal including Dhakaduring the time of Emperor Akbar. A few Rajput tribes from his army permanently settled around Dhaka and surrounding lands. Later, in the early 17th century, Islam Khan conquered all of Bengal. However, administration by governors appointed by the court of the Mughal Empire gave way to semi-independence of the area under the Nawabsof Murshidabad, who nominally respected the sovereignty of the Mughals in Delhi. After the weakening of the Mughal Empire with the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, Bengal was ruled independently by the Nawabs until 1757, when the region was annexed by the East India Company after the Battle of Plassey.

Bengal Renaissance

Bengal Renaissance refers to a socio-religious reform movement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the city of Kolkata by caste Hindus under the patronage of the British Raj and it created a reformed religion called Brahmodharma. The Bengal renaissance can be said to have started with reformer and humanitarian Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833), considered the "Father of the Bengal Renaissance", and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore(1861–1941), although there have been many stalwarts thereafter embodying particular aspects of the unique intellectual and creative output.[41] Nineteenth-century Bengal was a unique blend of religious and social reformers, scholars, literary giants, journalists, patriotic orators and scientists, all merging to form the image of a renaissance, and marked the transition from 'medieval' to 'modern'.[42]

Other figures have been considered to be part of the Renaissance. Swami Vivekananda is considered a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and America[43] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, and bringing Hinduism to the status of a world religion during the 1800s.[44] Jagadish Chandra Bose was a Bengali polymath: a physicist, biologist, botanist, archaeologist, and writer of science fiction[45] who pioneered the investigation of radio and microwaveoptics, made significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[46] He is considered one of the fathers of radio science,[47] and is also considered the father of Bengali science fiction. Satyendra Nath Bose was a Bengali physicist, specializing in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate. He is honoured as the namesake of the boson.

Independence movement

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samitiand Jugantar were dominant. Many of the early proponents of the independence struggle, and subsequent leaders in the movement were Bengalis such as Chittaranjan Das, Khwaja Salimullah, Surendranath Banerjea, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Titumir (Sayyid Mir Nisar Ali), Prafulla Chaki, A. K. Fazlul Huq, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, Bagha Jatin, Khudiram Bose, Surya Sen, Binoy-Badal-Dinesh, Sarojini Naidu, Aurobindo Ghosh, Rashbehari Bose, and Sachindranath Sanyal.

Some of these leaders, such as Netaji, who was born, raised and educated at Cuttack in Odisha did not subscribe to the view that non-violent civil disobedience was the best way to achieve Indian Independence, and were instrumental in armed resistance against the British force. Netaji was the co-founder and leader of the Indian National Army (distinct from the army of British India) that challenged British forces in several parts of India. He was also the head of state of a parallel regime, the Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind. Bengal was also the fostering ground for several prominent revolutionary organisations, the most notable of which was Anushilan Samiti. A number of Bengalis died during the independence movement and many were imprisoned in Cellular Jail, the notorious prison in Andaman.

Partitions of Bengal

The first partition in 1905 divided the Bengal region in British India into two provinces for administrative and development purposes. However, the partition stoked Hindu nationalism. This in turn led to the formation of the All India Muslim League in Dhaka in 1906 to represent the growing aspirations of the Muslimpopulation. The partition was annulled in 1912 after protests by the Indian National Congress and Hindu Mahasabha.

The breakdown of Hindu-Muslim unity in India drove the Muslim League to adopt the Lahore Resolution in 1943, calling the creation of "independent states" in eastern and northwestern British India. The resolution paved the way for the Partition of British India based on the Radcliffe Line in 1947, despite attempts to form a United Bengal state that was opposed by many people.

The legacy of partition has left lasting differences between the two sides of Bengal, most notably in linguistic accent and cuisine.

Bangladesh Liberation War

The rise of self-determination and Bengali nationalism movements in East Bengal (later East Pakistan), led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, culminated in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War against the Pakistani military junta. An estimated 3 million (3,000,000) people died in the conflict, particularly as a result of the 1971 Bangladesh genocide. The war caused millions of East Pakistani refugees to take shelter in India's Bengali state West Bengal, with Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal province, becoming the capital-in-exile of the Provisional Government of Bangladesh. The Mukti Bahini guerrilla forces waged a nine-month war against the Pakistani military. The conflict ended after the Indian Armed Forces intervened on the side of Bangladeshi forces in the final two weeks of the war, which ended with the Surrender of Pakistan and the liberation of Dhaka on 16 December 1971.

Culture

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

Cuisine

Bengali cuisine is the culinary style originating in Bengal, a region of South Asia which is now located in Bangladesh and West Bengal. Some Indian regions like Tripura, Shillong and the Barak Valley region of Assam (in India) also have large native Bengali populations and share this cuisine. With an emphasis on fish, vegetables, and milk served with rice as a staple diet, Bengali cuisine is known for its subtle flavours, and its huge spread of confectioneries and desserts. It also has the only traditionally developed multi-course tradition from the Indian subcontinent that is analogous in structure to the modern service à la russe style of French cuisine, with food served course-wise rather than all at once.

Festivals

The Bengalis celebrate many holidays and festivals. The Bengali proverb "Baro Mase Tero Parbon" ("Thirteen festivals in twelve months") indicates the abundance of festivity in the state. Durga Puja is solemnized as perhaps the most significant of all religious celebrations in West Bengal whereas in Bangladesh Eid-ul-Azha is the most significant religious festival.

Some major festivals celebrated are Durga Puja, Eid ul Fitr, Eid ul Azha, 21 February - Bengali language Day, Bengali New Year, Independence Day Of Bangladesh, Birthday of Kazi Nazrul Islam, Pohela Falgun, Birthday of Rabindranath Tagore, Death Anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore etc.

Language

Bengali or Bangla is the language native to the region of Bengal, which comprises present-day Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and southern Assam. It is written using the Bengali script. With about 250 million native and about 300 million total speakers worldwide, Bengali is one of the most spoken languages, ranked seventh in the world.[48][49] The National Anthem of Bangladesh, National Anthem of India, National Anthem of Sri Lanka and the national song of India were first composed in the Bengali language.

Along with other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, Bengali evolved circa 1000–1200 CE from eastern Middle Indo-Aryan dialects such as the Magadhi Prakrit and Pali, which developed from a dialect or group of dialects that were close, but not identical to, Vedic and Classical Sanskrit.

Literature

The earliest extant work in Bengali literature is the Charyapada, a collection of Buddhist mystic songs dating back to the 10th and 11th centuries. Thereafter, the timeline of Bengali literature is divided into two periods: medieval (1360–1800) and modern (1800–present). Bengali literature is one of the most enriched bodies of literature in Modern India and Bangladesh.

The first works in Bengali, written in new Bengali, appeared between 10th and 12th centuries C.E. It is generally known as the Charyapada. These are mystic songs composed by various Buddhist seer-poets: Luipada, Kanhapada, Kukkuripada, Chatilpada, Bhusukupada, Kamlipada, Dhendhanpada, Shantipada, Shabarapada, etc. The famous Bengali linguist Haraprasad Shastri discovered the palm-leaf Charyapada manuscript in the Nepal Royal Court Library in 1907.

The Middle Bengali Literature is a period in the history of Bengali literature dated from 15th to 18th centuries. Following the Mughal invasion of Bengal in the 13th century, literature in vernacular Bengali began to take shape. The oldest example of Middle Bengali Literature is believed to be Shreekrishna Kirtana by Boru Chandidas.

In the mid-19th century, Bengali literature gained momentum. During this period, the Bengali Pandits of Fort William College did the tedious work of translating text books in Bengali to help teach the British local languages including Bengali. This work played a role in the background in the evolution of Bengali prose.

Religion

The largest religions practiced in Bengal are Islam and Hinduism. According to 2014 US Department of State estimates, 89.9% of the population of Bangladesh follow Islam while 8.3% follow Hinduism. In West Bengal, Hindus are the majority with 70.54% of the population while Muslims comprise 27.01%. Other religious groups include Buddhists (compromising around 1% of the population in Bangladesh) and Christians.[32]

Media and music

Arts and science

Sport

Political culture

See also

- Bengali renaissance

- Ghosts in Bengali culture

- List of Bangladeshis

- List of Bengalis

- List of people from West Bengal

Rohingya people

| Ruáingga ရိုဟင်ဂျာ ﺭُﺍَࣺﻳﻨڠَ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 1,547,778[1]–2,000,000+[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Myanmar (Rakhine State), Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Thailand | |

| 1.0[3]–1.3 million[4][5][6] | |

| 500,000[7][8] | |

| 400,000[9] | |

| 200,000[10][11][12] | |

| 100,000[13] | |

| 40,070[14] | |

| 40,000[15][16] | |

| 11,941[17] | |

| 200[18] | |

| Languages | |

| Rohingya | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

The Rohingya people (/ˈroʊɪndʒə/, /ˈroʊhɪndʒə/, /ˈroʊɪŋjə/, or /ˈroʊhɪŋjə/)[19] are a stateless[20] Indo-Aryan people from Rakhine State, Myanmar, which they claim to be their homeland for generations. There are an estimated 1 million Rohingyas living in Myanmar.[21] The majority of them are Muslim and a minority are Hindu.[22][23][1][24][25] Described as "one of the most persecuted minorities in the world",[26] most of the Rohingya population are denied citizenship under the 1982 Burmese citizenship law,[27][28][29] which restricts full citizenship to British Indian migrants who settled after 1823.[30] The Rohingyas are also restricted from freedom of movement, state education and civil service jobs in Myanmar.[31][32] Despite promises of equality by Myanmar's independence leader Aung San,[33] the Rohingyas have faced military crackdowns in 1978, 1991–1992,[34] 2012, 2015 and 2016–2017. UN officials have described Myanmar's persecution of the Rohingya as ethnic cleansing,[35] while there have been warnings of an unfolding genocide.[36]Yanghee Lee, the UN special investigator on Myanmar, believes the country wants to expel its entire Rohingya population.[37]

Migration from the Indian subcontinent to Myanmar (formerly Burma) has taken place for centuries, including as part of the spread of Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam in the region. The historical region of Bengal (now divided between Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal) has historical and cultural links with Rakhine State (formerly Arakan). Bengali-speaking settlers are recorded in Arakan since at least the 17th century,[38] when the Kingdom of Mrauk Ureigned. The Rohingya language shares similarities with the Chittagonian dialect of Bengali. The term Rohingya, in the form of Rooinga, was recorded by the East India Company as early as 1799, but Burmese nationalists dispute its origins.[39] Indian migration increased during the period of British rule in Burma, as Burma was a part of British Indiauntil 1937.[40] Arakan had the largest percentage of British Indians in Burma.[41] British Indians in Arakan were involved in agriculture and trade. Their presence was resented by many in the Rakhine majority.[42]

During the Second World War, the Arakan massacres in 1942 involved communal violence between British-armed V Force Rohingya recruits and pro-Japanese Rakhines, which polarized the region along ethnic lines.[43] After Burmese independence in 1948, the region witnessed an Arkanese Independence Movement by Rakhine Buddhists and attempts by Rohingya Muslims to merge their territory with East Pakistan. In 1982, General Ne Win's government enacted the Burmese nationality law, which did not recognize the Rohingya as one of the "national races" of Burma, unlike the Kachin, Kayah, Karen, Chin, Bamar, Mon, Rakhine, Shan, Kaman and Zerbadee. As a result, the majority of the Rohingya population were rendered stateless.[1] In the years following the 8888 Uprising and return of martial law, the Burmese military junta launched a military crackdown against Rohingyas in 1991 and 1992, which caused 250,000 refugees to flee to neighboring Bangladesh and brought the two countries to the brink of war.[44][45]

The Rohingyas maintain the view that they are long standing residents of western Myanmar, and they also maintain the view that their community includes a mixture of precolonial and colonial settlers. The official stance of the Myanmar government, however, has been that they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. Myanmar's government does not recognize the term "Rohingya" and it prefers to refer to the community as Bengalis.[46][39][47][48][49][50][5][51]

Prior to the 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis and the military crackdown in 2016 and 2017, the Rohingya population in Myanmar was around 1.1 to 1.3 million[4][5][6][1][4] They reside mainly in the northern Rakhine townships, where they form 80–98% of the population.[51] Many Rohingyas have fled to southeastern Bangladesh, where there are 500,000 refugees,[52][53] as well as to India,[54] Thailand,[55] Malaysia,[56] Indonesia,[57] Saudi Arabia[58] and Pakistan.[59] More than 100,000 Rohingyas in Myanmar live in camps for internally displaced persons, and the authorities do not allow them to leave.[60][61] Probes by the UN have found evidence of increasing incitement of hatred and religious intolerance by "ultra-nationalist Buddhists" against Rohingyas while the Burmese security forces have been conducting "summary executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests and detentions, torture and ill-treatment and forced labour" against the community.[62] International media and human rightsorganizations have often described the Rohingyas as one of the most persecuted minorities in the world.[63][64][65] According to the United Nations, the human rights violations against the Rohingyas could be termed "crimes against humanity".[62][66]Rohingyas have received international attention in the wake of the 2012 Rakhine State riots, the 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis, and the 2016–17 military crackdown.

Contents

[hide]- 1Nomenclature

- 2History

- 2.1Kingdom of Mrauk U

- 2.2Burmese conquest

- 2.3British colonial rule

- 2.4World War II Japanese occupation and inter-communal violence

- 2.5After Burmese independence

- 2.6Post-independence immigration and Bangladesh Liberation War

- 2.7'Rohingya' movement (1990–present)

- 2.8Burmese juntas (1990–2011)

- 2.9Rakhine State riots and refugee crisis (2012–present)

- 2.10Historical demographics

- 3Demographics

- 4Language

- 5Religion

- 6Health

- 7Human rights and refugee status

- 8See also

- 9Notes

- 10References

- 11External links

Nomenclature

The Rohingya refer to themselves as Ruáingga /ɾuájŋɡa/. In the dominant languages of the region, they are known as rui hang gya (following the MLCTS) in Burmese: ရိုဟင်ဂျာ /ɹòhɪ̀ɴd͡ʑà/ and Rohingga in Bengali: রোহিঙ্গা /ɹohiŋɡa/. The term "Rohingya" comes from Rakhanga or Roshanga, the words for the state of Arakan.[67][68]