Is the world big enough for Huawei?

After climbing to the top of the smartphone market in its home country, the Chinese giant is taking off in Europe. But to challenge Apple and Samsung, the world’s no. 3 phonemaker needs to figure out how to reach American consumers — or how to live without them.

way up among the forests, fens,

and tundra of Finland, 5,000 miles from its headquarters in the balmy

south of China, Huawei is disrupting the world’s smartphone oligopoly.

As Nokia’s home country, Finland was once the center of the cell phone universe; later (along with most of the rest of the world) it became Apple and Samsung territory. But over the past 18 months, Huawei’s smartphone market share there has climbed from almost nothing to the summit. In the first quarter of 2016, Huawei sold 10 times as many phones as Apple in Finland, according to research firm IDC. And in October it soared ahead of Samsung for the market-share lead.

As Nokia’s home country, Finland was once the center of the cell phone universe; later (along with most of the rest of the world) it became Apple and Samsung territory. But over the past 18 months, Huawei’s smartphone market share there has climbed from almost nothing to the summit. In the first quarter of 2016, Huawei sold 10 times as many phones as Apple in Finland, according to research firm IDC. And in October it soared ahead of Samsung for the market-share lead.

Today

you can’t stride through Helsinki without encountering a Huawei

billboard. You can’t watch Jokerit, one of the country’s top hockey

teams, without seeing Huawei’s flower-in-bloom logo. And you can’t find

an electronics store where Huawei’s phones don’t outnumber Samsung’s and

Apple’s. “It was remarkable,” says IDC researcher Francisco Jeronimo,

who flew from London this winter to see for himself. “Their devices were

everywhere.”

Like many tech professionals, Jeronimo once expected that Apple and Samsung’s choke hold on high-end smartphones would last for many years to come. The companies have been No. 1 and No. 2 worldwide since 2011, and during that span they have never had a consistently strong third-place challenger. That gives the two more leverage to command outsize profit margins.

Enter Huawei—probably the most viable contender yet to loosen the giants’ grip. It’s a 170,000-employee company with $61 billion in sales, selling telecom equipment in 170 countries. Since 2014 it has been No. 1 globally in sales of the networking equipment that underpins telecommunication systems, taking the crown from Sweden’s Ericsson. And now its goal is to dominate the market for the phones themselves. It has taken big strides toward doing just that in China and in growing swaths of Europe—helped in those Western countries by side deals with wireless carriers that have not previously been reported.

Like many tech professionals, Jeronimo once expected that Apple and Samsung’s choke hold on high-end smartphones would last for many years to come. The companies have been No. 1 and No. 2 worldwide since 2011, and during that span they have never had a consistently strong third-place challenger. That gives the two more leverage to command outsize profit margins.

Enter Huawei—probably the most viable contender yet to loosen the giants’ grip. It’s a 170,000-employee company with $61 billion in sales, selling telecom equipment in 170 countries. Since 2014 it has been No. 1 globally in sales of the networking equipment that underpins telecommunication systems, taking the crown from Sweden’s Ericsson. And now its goal is to dominate the market for the phones themselves. It has taken big strides toward doing just that in China and in growing swaths of Europe—helped in those Western countries by side deals with wireless carriers that have not previously been reported.

Huawei

owes part of its success to a technical breadth that competitors can’t

match. It makes products along every point of wireless communications:

It builds the telecom networks that transmit signals, the chipsets

inside smartphones that interact with the networks, and the handsets

themselves, which it manufactures mostly in the sprawling city of

Shenzhen. It’s as if General Motors had paved the Interstate Highway

System, then started selling cars. Flush with cash from its networking

sales, Huawei spends more on research and development than its Chinese

rivals do, helping it build handsets whose quality is close to that of

iPhones and Galaxies.

The result: skyrocketing growth. In 2015, Huawei sold 108 million phones, ranking third worldwide. For 2016, it estimates that its shipments jumped 30%, to 140 million, and its phone revenue an estimated 40%, to 178 billion yuan ($26.5 billion), while the industry grew only by single digits globally. “It’s really grown fast,” says Gartner analyst CK Lu, who studies China’s smartphone makers. “From a global perspective, Huawei is the most successful Chinese brand.”

The result: skyrocketing growth. In 2015, Huawei sold 108 million phones, ranking third worldwide. For 2016, it estimates that its shipments jumped 30%, to 140 million, and its phone revenue an estimated 40%, to 178 billion yuan ($26.5 billion), while the industry grew only by single digits globally. “It’s really grown fast,” says Gartner analyst CK Lu, who studies China’s smartphone makers. “From a global perspective, Huawei is the most successful Chinese brand.”

An engineer adjusts Huawei antennas at a base station in Finland, where Huawei is now the top-selling smartphone maker.

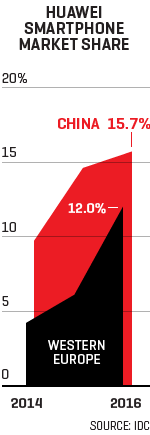

This

surge was long in the making. Loans from China’s government helped

Huawei build a network business in Africa and Latin America; the

experience it earned there helped it win networking-equipment deals

with major carriers in Europe. Now Huawei is selling its newest devices

for those same networks in Europe, where it doubled its smartphone

market share in the first nine months of 2016, to 12%. Huawei is the top

smartphone seller in Portugal and the Netherlands and the second

biggest in Italy, Poland, Hungary, and Spain. Like Apple and Samsung,

the company now unveils phones in splashy shows in Munich and London,

inviting hundreds of journalists and paying for many to attend.

In China, the world’s biggest country for smartphone sales, the fight for leadership resembles a game of king of the hill among closely matched domestic companies (see “China’s Smartphone Big Four”). But even there, Huawei’s ascendancy is striking. At the end of 2015, Huawei took the top spot for the first time, passing Apple and low-cost Xiaomi after boosting sales that year by more than 40%. The most recent market-share figures, depending on who’s measuring, show Huawei as either No. 1 or within a couple percentage points of the top.

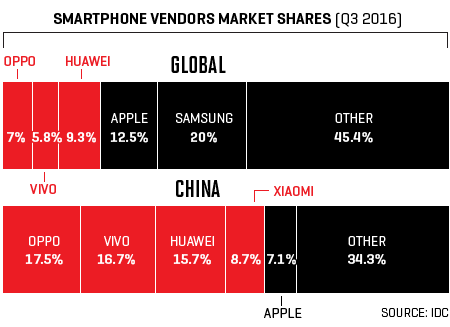

Immodestly, Huawei sees itself very soon passing Apple globally. “We are going to take [Apple] step by step, innovation by innovation,” Huawei’s consumer head, Richard Yu, told a reporter at a Munich product launch in November. He later told Fortune that Huawei would pass Apple in handsets sometime in 2018. That’s an ambitious but not unattainable goal: In the third quarter of 2016, Huawei’s 34 million smartphones shipped worldwide trailed Apple’s 46 million (with both far behind Samsung’s 73 million).

In China, the world’s biggest country for smartphone sales, the fight for leadership resembles a game of king of the hill among closely matched domestic companies (see “China’s Smartphone Big Four”). But even there, Huawei’s ascendancy is striking. At the end of 2015, Huawei took the top spot for the first time, passing Apple and low-cost Xiaomi after boosting sales that year by more than 40%. The most recent market-share figures, depending on who’s measuring, show Huawei as either No. 1 or within a couple percentage points of the top.

Immodestly, Huawei sees itself very soon passing Apple globally. “We are going to take [Apple] step by step, innovation by innovation,” Huawei’s consumer head, Richard Yu, told a reporter at a Munich product launch in November. He later told Fortune that Huawei would pass Apple in handsets sometime in 2018. That’s an ambitious but not unattainable goal: In the third quarter of 2016, Huawei’s 34 million smartphones shipped worldwide trailed Apple’s 46 million (with both far behind Samsung’s 73 million).

To

close that gap, however, Huawei will need to replicate its conquest of

Finland in many other, bigger markets—no easy feat. In much of Europe, Fortune

has learned, carriers that use Huawei’s networking equipment can get

significant discounts on its smartphones—side deals that have not

previously been reported. That’s a sales-boosting bonus other smartphone

makers can’t offer. But it’s also a tactic Huawei can’t use in the U.S.

Geopolitical tensions have kept Huawei from selling network equipment

in the States, which in turn has made the brand a stranger to American

wireless carriers. Not coincidentally, Huawei smartphones are a virtual

nonentity in the U.S., capturing less than 0.4% of the market.

Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei has talked about breaking into the U.S. time and again, former employees say. More $500-plus phones are sold here than anywhere else, making the country a gold mine of profits and prestige. But Huawei’s efforts so far have come up empty—and even the company doesn’t see that changing soon. So it finds itself at a crossroads: Can it really topple Apple or Samsung, or at least become their global peer, without making it big in America?

Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei has talked about breaking into the U.S. time and again, former employees say. More $500-plus phones are sold here than anywhere else, making the country a gold mine of profits and prestige. But Huawei’s efforts so far have come up empty—and even the company doesn’t see that changing soon. So it finds itself at a crossroads: Can it really topple Apple or Samsung, or at least become their global peer, without making it big in America?

Above,

from left: Richard Yu, head of Huawei’s consumer division, unveils the

Mate 9 phone at a launch event in Munich in November. Founder Ren

Zhengfei (right) gives Chinese President Xi Jinping a tour of Huawei’s

London offices.

until fairly recently,

even most Chinese consumers asked, “What’s Huawei?” For years the

company was one of many manufacturers making cheap, low-quality phones,

mostly “white label” products for telecom carriers that slapped their

own logos on the back. Huawei didn’t see a future making them: It even

tried to sell the business in 2008, but it couldn’t find a buyer.

Huawei’s own employees brought Samsung and Apple phones to work.

It was an embarrassment that founder Ren, who still holds the CEO title and directs strategy, almost certainly noticed. When Richard Yu, who had led Huawei’s European networking division, took over the consumer business in 2011, he knew the company needed to move into higher-quality devices. But it couldn’t happen overnight. “I remember the first year I took over the smartphone business, we sold less than 1 million,” Yu said in a recent interview at Huawei headquarters. Changing that has taken its toll: Yu carries the paunch of someone who spends two weeks a month on the road. He has quit running marathons, he says: “I’m too heavy.”

But Yu and his team were sprinters in using Huawei’s networking expertise to their advantage. Most of the world’s 1,000 smartphone manufacturers enjoy inexpensive access to what it takes to build a phone. Google provides Android software for the operating system; ARM, owned by Japan’s Softbank, licenses its design for chipsets. But the intellectual property of cellular networks—how phones talk to the network towers—is not shared, and that’s where Huawei focused.

It was an embarrassment that founder Ren, who still holds the CEO title and directs strategy, almost certainly noticed. When Richard Yu, who had led Huawei’s European networking division, took over the consumer business in 2011, he knew the company needed to move into higher-quality devices. But it couldn’t happen overnight. “I remember the first year I took over the smartphone business, we sold less than 1 million,” Yu said in a recent interview at Huawei headquarters. Changing that has taken its toll: Yu carries the paunch of someone who spends two weeks a month on the road. He has quit running marathons, he says: “I’m too heavy.”

But Yu and his team were sprinters in using Huawei’s networking expertise to their advantage. Most of the world’s 1,000 smartphone manufacturers enjoy inexpensive access to what it takes to build a phone. Google provides Android software for the operating system; ARM, owned by Japan’s Softbank, licenses its design for chipsets. But the intellectual property of cellular networks—how phones talk to the network towers—is not shared, and that’s where Huawei focused.

When

Yu took over, Qualcomm, Ericsson, Nokia, and other Western and Japanese

companies controlled 3G cellular network patents in the West,

effectively keeping Huawei out of many markets. Huawei, however, was

devoting its energy to patents and standards for the next generation: 4G

phones, run on networks 10 times as fast as 3G and better suited to an

always-updating app culture. “In the last three or four years, they’ve

invested a lot in [intellectual property],” says Neil Shah of

Counterpoint Research. “It’s almost on par with what Samsung or Apple

has done.” That eventually allowed Huawei to sell phones in Western

markets that Samsung and Apple had dominated, without cowering from IP

litigation.

By

2014, Huawei was producing the first Chinese smartphones that could

credibly claim quality as good as, and in some ways better than,

Samsung’s. Huawei’s phones were the first to include modems that let

Chinese users receive calls in basements and parking garages, where

other brands’ phones cut out. What they lacked in Apple-style cachet,

Huawei phones made up for with strong reception, powerful cameras

(Huawei’s P9 brought dual-camera systems to consumers a few months

before the iPhone 7 arrived), and slick designs. By the third quarter of

2016, 60% of Huawei’s smartphone shipments were mid- and high-priced

devices, a striking reversal of its past reliance on cheap handsets.

The cash generated by its $35-billion-a-year network-equipment business gave Huawei the resources to market phones to almost every consumer in China. And the company proved to be a nimble adapter that can sell both high and low. When a competing Chinese brand, Oppo, won over female buyers, Huawei countermoved with a new product line called Nova. When Xiaomi grabbed the world’s attention in 2014 with a business model of selling phones online, offering rock-bottom prices by eliminating retail overhead, Huawei reacted by building its own inexpensive online-only brand, called Honor. The lower-priced Honor made up 40% of Huawei’s total shipments in 2015, helping sales volume skyrocket. But the company still recorded high revenue growth thanks to higher-priced, Huawei-branded phones.

Conquering China was a way for Huawei to grow powerful, but not necessarily rich. Neil Mawston of Strategy Analytics estimates Huawei generated $200 million of smartphone operating profit in the third quarter; Apple’s smartphone profit was $8.5 billion. Huawei’s opportunities in China are limited by a constantly replenishing pool of competitors willing to lose money to build market share. “Our consumer business is profitable, but the margin compared with Apple and Samsung is very low,” Yu admits. Europe, where Huawei can sell higher-priced phones, is where the company sees an opportunity to grow it.

The cash generated by its $35-billion-a-year network-equipment business gave Huawei the resources to market phones to almost every consumer in China. And the company proved to be a nimble adapter that can sell both high and low. When a competing Chinese brand, Oppo, won over female buyers, Huawei countermoved with a new product line called Nova. When Xiaomi grabbed the world’s attention in 2014 with a business model of selling phones online, offering rock-bottom prices by eliminating retail overhead, Huawei reacted by building its own inexpensive online-only brand, called Honor. The lower-priced Honor made up 40% of Huawei’s total shipments in 2015, helping sales volume skyrocket. But the company still recorded high revenue growth thanks to higher-priced, Huawei-branded phones.

Conquering China was a way for Huawei to grow powerful, but not necessarily rich. Neil Mawston of Strategy Analytics estimates Huawei generated $200 million of smartphone operating profit in the third quarter; Apple’s smartphone profit was $8.5 billion. Huawei’s opportunities in China are limited by a constantly replenishing pool of competitors willing to lose money to build market share. “Our consumer business is profitable, but the margin compared with Apple and Samsung is very low,” Yu admits. Europe, where Huawei can sell higher-priced phones, is where the company sees an opportunity to grow it.

china's smartphone big four

Apple and Samsung dominate pricey smartphone sales, accounting for about a third of the market. But the next several names on the global bestseller list include four lower-cost Chinese competitors that collectively sell almost as many handsets as the big two. (Market share as of third quarter of 2016.)

Apple and Samsung dominate pricey smartphone sales, accounting for about a third of the market. But the next several names on the global bestseller list include four lower-cost Chinese competitors that collectively sell almost as many handsets as the big two. (Market share as of third quarter of 2016.)

xiaomi

Xiaomi’s

phones, all the rage in 2014, are falling out of favor almost as

quickly as they became hits, hurt by mediocre reviews and a lack of

retail distribution. The formerly online-sales-only company is making a

big push to open retail stores.

huawei

The

network-equipment giant sold an estimated $26.5 billion worth of phones

in 2016. It’s the only Chinese phonemaker whose devices are on par with

Samsung’s in quality—which helps explain its strong recent growth in

Europe.

Vivo

Marketing

for Oppo’s sister brand Vivo, also owned by Duan, focuses on its

smartphones’ camera, a major selling point in selfie-obsessed China.

Celebrity endorsements and its sponsorship of the NBA in China have

propelled the brand.

Oppo

Oppo,

owned by billionaire Duan Yong Ping, made its name selling cheaper

phones in rural China (where it has 200,000 retail locations) and

Southeast Asia. Its R9S looks like an exact copy of an iPhone 7—a

winning formula in China.

photos: courtesy of the companies

huawei might not

have earned that opportunity abroad if it hadn’t been considered a

national champion at home. Ren Zhengfei, a former army engineer, founded

the company in Shenzhen in 1987 to sell telecom switches. Officially,

Huawei has kept China’s government at arm’s length. According to a story

widely reported in Chinese media and sourced to a government planning

official, former Premier Zhu Rongji approached Ren around 2000, when

Huawei was expanding rapidly, and told Ren he could arrange a loan of

300 million yuan ($35 million). Ren turned it down: He didn’t want to be

hooked too tightly to the government.

But a less direct form of state support has benefited Huawei. The China Development Bank, tasked with supporting Chinese companies’ expansion abroad, is the world’s largest, with $1.8 trillion in assets (bigger than the controversial Export-Import Bank of the U.S. by a multiple of 64). Just after Christmas in 2004, CDB signed a $10 billion agreement with Huawei to provide loans to its customers in Africa and Latin America; the credit level later rose to $30 billion.

“If there had been no government policy to protect [national companies], Huawei would no longer exist,” Ren has said. Huawei’s revenue soared after the loan guarantees kicked in; overall, its sales nearly quintupled from $3.8 billion in 2004 to $18.3 billion in 2008. Huawei was undercutting competitors’ prices by anywhere from 10% to 30%, and Huawei executives routinely traveled with Chinese government officials on dealmaking trips, according to Nathaniel Ahrens, who studied the company for the Center for Strategic International Studies in Washington, D.C.

The experience gained in Africa and Latin America and other emerging markets paved the way for Huawei’s acceleration in Europe. Huawei rose to international prominence in 2005 when it struck a global equipment deal with U.K.-based multinational carrier Vodafone. By 2007 it had deals with all the major European carriers. And by 2015, Huawei’s smartphone quality was up to the European carriers’ quality standards—ready to be deployed on the very networks that Huawei equipment helped build.

But a less direct form of state support has benefited Huawei. The China Development Bank, tasked with supporting Chinese companies’ expansion abroad, is the world’s largest, with $1.8 trillion in assets (bigger than the controversial Export-Import Bank of the U.S. by a multiple of 64). Just after Christmas in 2004, CDB signed a $10 billion agreement with Huawei to provide loans to its customers in Africa and Latin America; the credit level later rose to $30 billion.

“If there had been no government policy to protect [national companies], Huawei would no longer exist,” Ren has said. Huawei’s revenue soared after the loan guarantees kicked in; overall, its sales nearly quintupled from $3.8 billion in 2004 to $18.3 billion in 2008. Huawei was undercutting competitors’ prices by anywhere from 10% to 30%, and Huawei executives routinely traveled with Chinese government officials on dealmaking trips, according to Nathaniel Ahrens, who studied the company for the Center for Strategic International Studies in Washington, D.C.

The experience gained in Africa and Latin America and other emerging markets paved the way for Huawei’s acceleration in Europe. Huawei rose to international prominence in 2005 when it struck a global equipment deal with U.K.-based multinational carrier Vodafone. By 2007 it had deals with all the major European carriers. And by 2015, Huawei’s smartphone quality was up to the European carriers’ quality standards—ready to be deployed on the very networks that Huawei equipment helped build.

That’s

where Huawei’s breadth gives it a major edge in the smartphone market

today, says Jeronimo, the IDC research director, who previously worked

at Korean conglomerate LG selling its smartphones to Vodafone. Huawei

offers carriers vouchers worth a percentage of their spending on network

equipment, which they can use either for network services or

smartphones from Huawei, Jeronimo has confirmed with at least one

European wireless operator. “If you don’t buy the Huawei network, you

pay a certain price,” Jeronimo says. “If you do buy a Huawei network,

then you get a better price.” If a carrier uses the discount on Huawei

phones, the savings can be several percentage points of the total cost,

or millions of dollars. “In the end it’s a very strong incentive for

carriers to buy Huawei devices,” Jeronimo says. Since they make a bigger

profit when they sell or lease them to consumers, and since Huawei’s

phone quality has improved, those phones get better marketing placement.

It’s not an incentive the companies are eager to discuss: In a hot, competitive market, they tightly guard the financial details of their partnerships. Huawei told Fortune it wouldn’t comment on “confidential business arrangements with customers.” Huawei network customers Vodafone, T-Mobile (of Germany), and Orange (France) also declined to comment. A spokesman for Elisa, one of Finland’s largest wireless providers, said its core relationship with Huawei has been built on devices, including USB Internet dongles and smartphones, but added, “We cannot go into commercial details regarding our cooperation.”

Whatever the specifics may be, Huawei’s success in Europe illustrates just how important strong relationships with wireless carriers have become to smartphone makers. And it also helps explain Huawei’s biggest dilemma: its continued irrelevance in the U.S.

It’s not an incentive the companies are eager to discuss: In a hot, competitive market, they tightly guard the financial details of their partnerships. Huawei told Fortune it wouldn’t comment on “confidential business arrangements with customers.” Huawei network customers Vodafone, T-Mobile (of Germany), and Orange (France) also declined to comment. A spokesman for Elisa, one of Finland’s largest wireless providers, said its core relationship with Huawei has been built on devices, including USB Internet dongles and smartphones, but added, “We cannot go into commercial details regarding our cooperation.”

Whatever the specifics may be, Huawei’s success in Europe illustrates just how important strong relationships with wireless carriers have become to smartphone makers. And it also helps explain Huawei’s biggest dilemma: its continued irrelevance in the U.S.

In

the U.S., huawei phones don’t crack the Top 10 in sales. “The U.S.

Remains their bottleneck,” says an analyst. “It will take time.”

in the states, Huawei’s smartphones don’t crack the top 10, trailing even who-dat? companies

like BLU and OnePlus. A direct-sales website, GetHuawei.com, has gotten

nowhere. Shoppers can buy Huawei phones at Best Buy or on Walmart.com,

but few do. Huawei sold just 153,000 handsets in the U.S. in the third

quarter of 2016; Apple sold nearly 12 million.

Huawei’s ties to the Chinese government and presumed ties to China’s army have plagued its U.S. business for a decade. Its attempted acquisitions of U.S. network-server and switch companies have been blocked twice, in 2007 and 2010, by the White House Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., which can invoke national-security concerns to prevent such deals. In 2010, Republican senators thwarted Huawei’s bid to sell networking equipment to Sprint Nextel. And a 2012 report from the House Committee on Intelligence raised concerns about Huawei’s government ties. Despite being short on evidence, the committee’s recommendation that U.S. companies avoid Huawei’s equipment remains influential, and a Donald Trump administration appears unlikely to be more accommodating.

Unable to sell equipment to them, Huawei doesn’t have the relationships with American wireless companies that it enjoys in Europe. None of the U.S. “big four”—Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, and Sprint—has cut a deal with Huawei. Since carriers account for 80% to 90% of smartphone sales in the U.S., Huawei isn’t making an impression on consumers, and Americans can’t find Huawei in the carrier-branded stores, kiosks, and websites where most buy their gear.

Yu, Huawei’s consumer chief, recognizes that Huawei needs to build those relationships from scratch. “The past five years we were not taking the right strategy,” Yu says. “We didn’t have the right people.” Huawei recently hired Michelle Xiong, a former Verizon wireless executive with experience negotiating with device makers, to help sell Huawei’s smartphones. But a Huawei staffer cautions that any carrier agreement is at least a year away, pushing meaningful success in the U.S. at least three years down the road. (Verizon had no comment on its relationship with Huawei; AT&T did not respond to requests for comment.) “The U.S. remains their bottleneck,” says Shah, the Counterpoint analyst. “It will take time.”

The bottleneck hasn’t choked Huawei’s ambitions. “We want to grow into top two [in] market share, and, in the future, top one by 2021,” Yu says matter-of-factly at the end of an interview.

Minus big American sales, Huawei may get a boost from a technological breakthrough—in 5G wireless service. Today, 5G is more imagined than real (standards won’t be finalized until 2020), but the technology promises speeds of 60 times that of current 4G networks. Even more important is the number of connected devices it can support—an estimated 1,000 times the connections of a 4G network, which would make 5G the architecture for a pending rush of Internet-connected cars, homes, businesses, and smart cities. Analysts see Huawei, along with Sweden’s Ericsson, as an early leader in building that network.

In Finland in November, the carrier Elisa claimed a world record: It sent data through its network at 1.9 gigabits per second, a speed capable of supporting virtual reality without glitches or the fastest movie streaming users could imagine. The speed was reached on a test network—built by Huawei. It was a glimpse of the next information superhighway. And with success in the U.S. a distant possibility at best, it may also be a glimpse of the fast-lane innovations Huawei will need if it’s ever going to catch Samsung and Apple.

A version of this article appears in the February 1, 2017 issue of Fortune.

Huawei’s ties to the Chinese government and presumed ties to China’s army have plagued its U.S. business for a decade. Its attempted acquisitions of U.S. network-server and switch companies have been blocked twice, in 2007 and 2010, by the White House Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., which can invoke national-security concerns to prevent such deals. In 2010, Republican senators thwarted Huawei’s bid to sell networking equipment to Sprint Nextel. And a 2012 report from the House Committee on Intelligence raised concerns about Huawei’s government ties. Despite being short on evidence, the committee’s recommendation that U.S. companies avoid Huawei’s equipment remains influential, and a Donald Trump administration appears unlikely to be more accommodating.

Unable to sell equipment to them, Huawei doesn’t have the relationships with American wireless companies that it enjoys in Europe. None of the U.S. “big four”—Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, and Sprint—has cut a deal with Huawei. Since carriers account for 80% to 90% of smartphone sales in the U.S., Huawei isn’t making an impression on consumers, and Americans can’t find Huawei in the carrier-branded stores, kiosks, and websites where most buy their gear.

Yu, Huawei’s consumer chief, recognizes that Huawei needs to build those relationships from scratch. “The past five years we were not taking the right strategy,” Yu says. “We didn’t have the right people.” Huawei recently hired Michelle Xiong, a former Verizon wireless executive with experience negotiating with device makers, to help sell Huawei’s smartphones. But a Huawei staffer cautions that any carrier agreement is at least a year away, pushing meaningful success in the U.S. at least three years down the road. (Verizon had no comment on its relationship with Huawei; AT&T did not respond to requests for comment.) “The U.S. remains their bottleneck,” says Shah, the Counterpoint analyst. “It will take time.”

The bottleneck hasn’t choked Huawei’s ambitions. “We want to grow into top two [in] market share, and, in the future, top one by 2021,” Yu says matter-of-factly at the end of an interview.

Minus big American sales, Huawei may get a boost from a technological breakthrough—in 5G wireless service. Today, 5G is more imagined than real (standards won’t be finalized until 2020), but the technology promises speeds of 60 times that of current 4G networks. Even more important is the number of connected devices it can support—an estimated 1,000 times the connections of a 4G network, which would make 5G the architecture for a pending rush of Internet-connected cars, homes, businesses, and smart cities. Analysts see Huawei, along with Sweden’s Ericsson, as an early leader in building that network.

In Finland in November, the carrier Elisa claimed a world record: It sent data through its network at 1.9 gigabits per second, a speed capable of supporting virtual reality without glitches or the fastest movie streaming users could imagine. The speed was reached on a test network—built by Huawei. It was a glimpse of the next information superhighway. And with success in the U.S. a distant possibility at best, it may also be a glimpse of the fast-lane innovations Huawei will need if it’s ever going to catch Samsung and Apple.

A version of this article appears in the February 1, 2017 issue of Fortune.

Ref:http://fortune.com/huawei-china-smartphone/

No comments:

Post a Comment